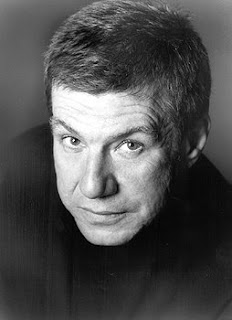

Filmmaker John McTiernan.

Filmmaker John McTiernan. JOHN MCTIERNAN:

AFFAIRS OF THE CROWN

By

Alex Simon

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the August 1999 issue of Venice Magazine.

John McTiernan was born January 8, 1951 in Albany, New York. The son of an attorney, the family moved to a rural farm community in upstate New York after his father became ill. McTiernan attended Exeter prep school during his high school years, and was admitted to Julliard with the intention of studying theater directing. While there, McTiernan quickly discovered that his true love was film and enrolled in an experimental film program at the State University of New York, later moving on to the American Film Institute for graduate school, where he studied under the tutelage of the great Czech director Jan Kadar.

After spending the next decade making a name for himself as a talented TV commercial director, McTiernan landed his feature debut with Nomads in 1986. The eerie supernatural thriller, his first collaboration with a young television actor named Pierce Brosnan, received mixed reviews and didn’t burn up the box office, but McTiernan was singled out for his sure hand and distinctive directorial eye, enough so that producer Joel Silver recruited McTiernan to direct the blockbuster Predator (1987), the high-octane Arnold Schwarzenegger thriller that combined The Most Dangerous Game (1932) with Alien (1979), to create a box office smash that also helped solidify Schwarzenegger as a major box office draw. McTiernan became one of the hottest directors in Hollywood after his next feature, Die Hard (1988), reinvented the action-adventure genre and went on to become one of the most-imitated films in history, and helped to establish another action hero screen icon in Bruce Willis. McTiernan flexed his intellectual muscles and kept the explosions and gunfire to a minimum with his taut adaptation of Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October (1990). The Alec Baldwin-Sean Connery starrer, was a box office champ the year of its release and, many feel, remains the best of the three big screen Clancy adaptations. McTiernan made a more personal picture with Medicine Man, (1992), again teaming with Connery in the tale of a scientist in the Latin American rain forest. Although many regard The Last Action Hero (1993) as a major stumbling block in McTiernan’s brilliant career, the film went on to gross over $100 million worldwide. McTiernan re-teamed with Bruce Willis for the third Die Hard installment, Die Hard: With a Vengeance in 1995, and re-established his box office clout in doing so.

McTiernan’s latest film will undoubtedly be regarded as his finest work thus far. There are so many good things to say about McTiernan’s remake of 1968’s Steve McQueen classic The Thomas Crown Affair, that an entire sonnet could be composed to extol its virtues. Here’s just a few: 1) It’s made with intelligent adults in mind, not 15 year-old boys. 2) Rene Russo is living proof that a woman need not be a 22 year-old refugee from the WB network to burn up the screen with her sexuality 3) It’s the only remake I can think of (since John Huston made the third, and definitive version of The Maltese Falcon in 1941) that is better than the original. Pierce Brosnan ably fills McQueen’s shoes as the super cool, ultra rich Thomas Crown, who gets his kicks pulling daring heists in his spare time. Russo, in one of the most free-spirited displays of healthy sexuality in screen history, assumes Faye Dunaway’s former role as insurance investigator Catherine Banning, who intends to catch Crown in the act, and instead finds herself caught up in an act all their own. Leave the kiddies at home and don’t miss this smart, sexy winner. The MGM release is currently playing all over southern California.

In person, John McTiernan doesn’t come across as a director of action heroes, or a man who has blown up glass skyscrapers to thrill the masses. McTiernan is a man who almost resembles a character out of Hemingway, a man’s man whose speech style is both verbose and lean. Lean back and dig some of his verbosity.

Your version of The Thomas Crown Affair is one of the only remakes I've seen that surpasses the original.

John McTiernan: That's very kind, but part of making movies is the ability to capture the time in which they were made. I think the original was a product of its time (1968), so it's not fair to say that the original doesn't hold up by today's standards. The more something is a piece of its time, the it's going to date afterwards. So I think that to say the original is dated is almost a compliment to it. It says that it really captured the era in which it was made, which I think it did. It's funny, if you remade a movie in 1968 that was originally made in 1938, nobody would think twice, because you'd be spanning this chasm that made it another world. Maybe it's because there's such a huge population of baby boomers that still think of 1968 as being a fairly recent time that we don't feel that distance now. When you look at the original now, at the time it was so cutting-edge, and now that sort of high-style cinema verite, which today looks quite theatrical trying to give the illusion that it's real. I wanted to do a remake that wasn't quite a remake, but a compliment to the original, a bookend, a sequel...I don't know what the hell you'd call it. (laughs) I wanted to give a sense that this movie respected that one.

I think the best remakes are the ones that are re-imagined. Literal remakes have never worked.

No, they don't. You take a portion of the story and go with that, then it can work. No one thinks twice of doing Shakespeare productions every year. It's not "We're re-doing MacBeth," because (Shakespeare) is part of our landscape, so the idea that those plays keep getting renewed is perfectly normal. And I think that eventually, people will start doing that with movies, because there's enough of a history of movies now.

The other thing I liked about your film was the fact that it was made with adults in mind.

Yeah, but interestingly enough, we scored just as high with young men as we did with adults, and we figured out that it was the whole Mrs. Robinson thing, with young men having the hots for Rene.

Another great thing about this movie: it shows a woman who's in her 40's, who still incredibly sexy and very comfortable with it. It's not a 22 year-old lead actress with a 50 year-old leading man. That was very refreshing to see.

I didn't know that Rene was in her 40's until she started doing interviews about it, bragging about it! Her age is never an issue in the film, but she's making an issue of it now. I'd better stop her! (laughs)

But that's what 40-50 looks like nowadays. It's not like it was 20-30 years ago. People are staying youthful longer.

Yeah, that whole dynamic has changed. Now that time period of 45-50 is when a woman is at her hottest, I agree. There's a great line about that: "The most important sexual organ is the eight inches from here (indicates his ears) to here." It takes a while for that to develop. (laughs)

It was also nice to see Rene Russo playing a sexy, elegant woman, as opposed to a tomboy who happens to be sexy.

Yeah, that's true. Her whole persona prior to this was of a gorgeous woman who didn't care that she was gorgeous and just wanted to be one of the guys. Because I wanted to make a love story, and not a caper film, the audience had to fall in love with the characters, too. Both Rene and Pierce have this quality. Even when they've played bad guys, the audience can sense that somewhere in there is a good person, because they can see it in their eyes. You can't lie about that. There are many great actors, who are great-looking who can never play a lead because there's something in their eyes that makes they audience go "Well...I don't know if I trust him. I don't know that he represents me." That's one of the few aspects of this craft that's God-given and can't be learned. So I was looking for two people with whom the audience could have a secret with. For the first half of the film, they're both real crocodiles, very difficult to sidle up with. They're both dangerous people, but the audience has a secret where they just know "You know what, underneath that there's a really great guy, and underneath Rene's front there's a really sweet girl."

This is the second film you've done with Pierce. I've always felt that he was an underused actor, in the sense that many filmmakers rarely let him act, but just wanted him to stand there and look pretty.

They never knew how good he is, how smart he is. He's changed very little since I worked with him before, which is good. I think in many ways some of the (hardships and tragedies) he's endured over the past decade have helped to season him in a good way. He's not so boyish anymore, and I think as he gets older, he'll just become even more impressive. I kept beating up his make-up man on this saying 'Leave him alone! Quit trying to make him pretty. Let me see the age on his face. Let me see the hard edge around him.' He's just getting on the cusp of that now, just getting enough steel in his face, enough grit.

Remember how scary he was in his first role (The Long Good Friday, 1981)? It was his boyishness that made him scary (playing an IRA assassin).

God, he was great in that! Remember that last scene with him just staring at Bob Hoskins in that car?! He was brilliant in that film, and it was his the sweetness and boyishness of his face that made him so scary. There were people in my family who worked for Michael Collins back during the Troubles. One of my relatives had to disappear and come to the States. This man was the most deferential, wonderful man who had the warmest smile, and the reason he fled to the States is he dropped an egg basket full of hand grenades into the lap of a British General. I knew him as a very old man, but he was so sweet, and so polite...it was as if he wouldn't have stepped on a crack in the sidewalk, he led such a straight and narrow life. But that was where he came from.

Let's talk about where you came from.

My dad was a lawyer and became ill for quite some time, so my mother, sister and I moved back with her parents on a farm in upstate New York. I still live on a farm today, in Wyoming. I went to Exeter for prep school, which was quite terrifying for me. Here I was, this middle class kid, not very cosmopolitan, in this upper crust place, and it terrified me. I did well academically, but didn't fit in at all socially. I became intensely interested in film, so much so that I almost didn't go to college so I could make films. I went to Julliard, then to the State University of New York, which had an experimental film program going on. I was one of the only film students that wasn't stoned the whole time (laughs), so I ended up using most of the money and resources they offered. Then I went to the AFI after that.

Was there any one film that ignited your interest?

No, but I remember when I decided that that's what I was going to do. I went about it like it was reverse engineering. I knew that I had to go and learn what a movie was, not just my experience of going and watching a movie. So I went and sat in Truffaut's Day for Night (1972), watched it for three days straight, eight hours at a time and memorized it shot-for-shot. I got past the story, all the original and secondary experience, so I could study what it was that I was really watching. Film is really sort of a chain that's really linear. Yet when it's all strung together, it just sort of feels like an experience. It takes quite a while to be able to deconstruct that experience to figure out what you really saw.

Tell us about your experience at AFI.

One of the sort of perks there is they don't have grades, but they would take the person they felt was the most likely to succeed, and they'd give him or her to the filmmaker in residence as an assistant. So I worked for Jan Kadar, the great Czech filmmaker. If you read Hemingway, half of the information you get is in this style of how he tells you, his prose style. It's not literally the events he recounts, it's how he recounts them, which appears to be obsessively simple in nature. There's a hint to what people are thinking, but he doesn't go off into these vast internal monologues. That's what Jan's style was like. He used to make me sit down and learn movies shot-for-shot. And we'd watch films by some great masters, like Kubrick and Fellini and Jan would say "See! Look what he did wrong there! That's wrong! Do you understand why it's wrong?" And I'd say 'What's wrong with it? It's a nice shot.' "No, no," Jan would say, "visually, it's out of key." He had a whole sense that you had to approach filmmaking like you were composing a piece of music. It wasn't about making a translation from a literary source. To decide what the next note is in a piece of music, you don't think about the plot, or what it means, you think about: what does it sound like? Is it in the right rhythm, the right key? So the montage in a film needs to be in the same key, and if you're going to change key, you'd better transpose it into the other key, as if you were composing a concerto. In color and lighting also, there are visual melodies. It's weird because I'm sort of known as an "action guy," who gets 10,000 machine guns and blows things up. But I cut my teeth on very esoteric European films. Maybe what Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Starship Troopers) and I did was to take the technology that the Europeans developed in the 60's and started applying it to mass market American movies. Paul has an expressive narrator in that his camera is an active, expressive person. I think it's a very angry, very fiery person. If you think about American films before the European influence in the 1960's, there was no active narrator. With a few exceptions, the camera just photographed the action and didn't really have a distinctive voice of its own.

Let's talk about some of your other films, starting with your first, Nomads. What was it like making the jump into features?

Well, I'd done a little feature called Tales of the 22nd Century that got me into AFI. I only did commercials to support myself, really, while I was in school. It was sort of a jump in the other direction, because I started making films, then moved into commercial directing. So going back to making a feature wasn't that big a jump, really.

I know you didn't go into Die Hard thinking you were going to re-invent the action-adventure genre. What were you aiming for?

I think to try to make a thriller that could be jacked up a notch with a great story underneath it. There were also a lot of technical things I was really anxious to do, like have a really active camera. When I broke into the business, the rule was that you weren't allowed to cut a moving camera shot into another moving camera shot. At the beginning of Red October, I had to fire an Academy Award-winning editor, because he literally didn't know how to cut the stuff. He didn't know how to deal with a moving camera and an active narrator.

With Red October were there different challenges filming an existing novel than from an original script?

No, in many ways it just makes it better. I enjoy working from a novel.

I really enjoyed Alec Baldwin's interpretation of Jack Ryan. What was it like working with him.

Terrific. He's tremendously intelligent, another good Irish-American kid. (laughs) We had a great time. He's fiery, and somewhere behind the fire is a worry about something, if you can find out what he's really worried about.

You opted not to do the second Die Hard, as well as the two Tom Clancy sequels. Why is that?

Well, they wanted to do Patriot Games, which had the villains as the Irish Republican Army. Both Alec and I, as Irish-Americans, were a bit uncomfortable with that, since it's our heritage. They had another script (Clear and Present Danger) that both Alec and I wanted to do, and for various reasons we decided not to. With Die Hard, I guess I just found myself bumping heads with Joel Silver a lot.

You've done two pictures with Sean Connery. What was he like to work with?

I knew I was doing alright with him when he began calling me 'boy.' That's sort of his mark of approval. At the end of the night he'd say "Good night, boy." (laughs) Sean loves movies, really knows a lot about them. And he really liked my style of working, the way I like to shoot. So it was very easy to work with him.

Medicine Man seems like it would have been a tremendously difficult shoot.

It was. We had all sorts of rigs mounted in the trees, all over the jungle. We probably spent three weeks working 125 feet above the forest floor.

What did you learn in making The Last Action Hero?

Well first of all, I learned the idiocy of releasing a film the week after Jurassic Park (laughs). And also that a studio will do anything do push a movie out, even if it's unfinished, which it was. It's largely unedited and large portions of it still appear exactly as it was when it left the camera. It wasn't ready yet. I don't know that I'll ever get the chance to go back to it. It's like having a model with an extra 20 pounds on her. There's a really neat movie in there. In order to get a sense of fun that was clear to the audience, it needed tightening, and it needed another month in editing to do that.

Any advice for first-time directors?

It's the same thing of how you get to Carnegie Hall: practice, practice, practice. (laughs) Also, I'd say get a hold of a video camera and just shoot as much as you can, of anything. If you have a script, get a couple actors together and shoot two pages from the script, then edit the footage on a really basic video editing program. It takes as long to develop a prose style on film as it does a prose style in writing, so it's crucial to practice whenever and however you can.

John McTiernan is the legend!!!

ReplyDeleteYes he is

ReplyDelete