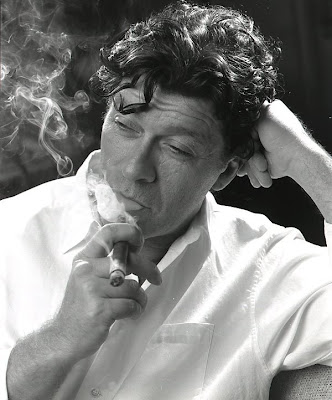

Musician and actor Robbie Robertson.

Musician and actor Robbie Robertson. ROBBIE ROBERTSON IS MAKING SOME NOISE

by

Alex Simon

Editor’s Note: The following article originally appeared in the December 1998 issue of Venice Magazine.

Robbie Robertson achieved international fame and prominence with his groundbreaking work in the legendary 60's and early 70's rock group The Band. Known for their innovative blend of roots rock n' roll, blues and country, The Band forged the way for such eclectic groups as The Eagles, R.E.M., and Hootie and the Blowfish with their blend of musical styles and genres. Born Jamie Robbie Robertson on July 5, 1943 in Toronto, Canada to an Anglo father and Native American mother from the Mohawk tribe, Robertson was taught to play the guitar by relatives living on the Six Nations Indian Reservation where his mother was raised, outside Toronto. He spent his teens in various rock groups around Toronto, finally joining up with Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks in 1960. The group also included future Band members Levon Helm, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson. During his time with the Hawks, Robertson found time to work with other musicians as well, most notably Bob Dylan on his classic Blonde On Blonde album. The Hawks became The Band in 1968, and gained instant fame with their debut LP, Music From Big Pink. The group disbanded in 1977, documented in Martin Scorsese's now-legendary film The Last Waltz (1978). Robertson has led a troubadour's life since The Band's break-up, continuing to record new music, act in films, and work with pal Scorsese on the music scores of some of his most famous works, including Raging Bull, King of Comedy, Color of Money, and Casino.

Robertson has never let his fascination with different types of music leave him, this being evident with is newest album release, Contact From the Underworld of Redboy, which finds Robertson re-embracing the music of his Native American roots, and the hour-long documentary Robbie Robertson: Making a Noise, which airs on PBS this month. The film documents Robertson's return to the Six Nations Indian Reservation outside Toronto, Canada, reuniting with friends and relatives, many of whom he hadn't seen in over 30 years. Robertson is joined by other notable Native American musicians, such as Rita Coolidge, Buffy Saint-Marie, John Trudell, and Ulali. Robertson sat down recently to discuss his work, past, present, and future.

I thought Making a Noise was really terrific. It gave me an appreciation of Native American music that I didn't previously have.

ROBBIE ROBERTSON: Yeah, (the filmmakers) did a really terrific job. Making something like this is a little more delicate and complicated than it might seem from the outside. Several people in the Native American community couldn't do it, because they have to answer to their elders, and in Indian country, you do not cross that line. It's a very, very sensitive place. You don't want people from the outside there. It's like it's bad jiu-jiu.

So it's a very closed culture in that sense.

It is, and you have to keep in mind that for so long, a lot of this musicality and the culture has been very private, and in some cases sacred and secret. Like in the case of the peyote ceremony, it's been illegal for 100 years and now has just kind of opened up...after people have been punished and thrown in jail for the past 100 years, just for practicing their religion, that takes kind of a long time to believe again that it's okay to practice it openly. The Native American Church is still very sensitive about it.

When you say the Native American Church, is that a Native American religion that's actually organized like a white church would be?

There's this thing called the N.A.C. and it's an organization that goes from up in Canada, to Arizona, over to Oklahoma, all the way down to Mexico, it's called the "Peyote Belt." There are many nations in this area that are part of the N.A.C. which is another way of saying the peyote religion. I went to a peyote ceremonial a couple months back with this friend of mine, John Trudell, who's a poet and activist. And we went to meet Primo and Mike, these two young guys that I work with. And their attitude is "Come on, it's a new millennium. It's time to share these things, to let people know how beautiful and simple this whole thing is, that it's not threatening. That it's a beautiful way for us to take this sacred medicine and connect with our creator. And this is the way we've been doing it for hundreds and hundreds of years." The older people who may have gotten in trouble for it, are a little less trusting. So right now it's a little in between the two beliefs...There's this guy up in Canada who's the head of the peyote church. He has to approve everything to do with the ceremonial. And during the ceremony, they have a log, where they write down everyone's name, what their affiliation with the church is, what your native connection is...So it's not a lose thing because of the repercussions that vary from state-to-state and district-to-district. At this point, the doors to this world have opened just a little bit for the first time. But even me, going back to where I come from, I have to get permission from everybody to do this. They're gunshy.

Let's talk about your own personal journey. You grew up in Toronto, right?

In my early years I grew up going back and forth between the two worlds. But when I got older, I didn't go as much into Six Nations because I was starting to go deeper into my own existence and own discovery.

What was it like going between those two worlds? Did you encounter a lot of prejudice?

I didn't encounter a lot of prejudice because I could pass (as all-white)...the only predominant time was when I was playing with a couple of my cousins and they had come to Toronto to visit with me. We were playing up at these railroad tracks by this field. One of the things that impressed me so much as a little boy, was how my cousins could see a tree, a branch and could jump up, snap the branch off, and within moments, make the most beautiful weapon you've ever seen! It's such a boy thing! It's awful, but boys love it! So one of my cousins made a bow for me and I was trying it out, hanging by the field. Then these older kids showed up, and because my cousins looked more like Indians than I did, these older kids said "Hey redboy! Where you goin' with that bow in your hand?" And I saw my cousins, and their heads just dropped. And a chill ran through me, from them. I got to feel something through them this time, and it was this sick feeling. You could feel hate in it. And it's stayed with me my whole life. So when I was making this record, I wanted to be blatantly honest, and thought "This is a time for me to bring this out, and get it out of my system." Because of a certain boldness that I wanted to get across in this, that's why I used ("Redboy") in the title. I thought, "I can say this now, and it's healthy for me to say this." I grew up with a philosophy from my mother, which was "Be proud that you're an Indian, but be careful who you tell." And when my mother was growing up, the idea was "The whole Indian thing, it's gotta go." When my mother left the reservation to come to Toronto to live with her aunt, her aunt told her "Don't you tell anybody you're from the reservation. Let them think whatever they want, that you're from another country, but don't tell anyone unless you absolutely have to."

So they made this whole generation of people ashamed of who they were.

More than ashamed. It was like "It's over. You have to become white."

A lot of the archival footage and photos you used in the film showing these Indian kids in their lettermen's sweaters with short haircuts trying to look like Wally and the Beav', were such ironic images.

That's just it. They were trying to be white. This guy I met while we were shooting the film was telling me that as a kid he was taken away from his parents, sent off to a school to be trained to become a white person. He went to this school and within a couple weeks, he was so ashamed of his heritage, that one day he found himself in the boy's bathroom with this bucket of soapwater and an iron brush, trying to wash the Indian off his skin. He said he scrubbed himself raw all over his body trying to "wash the Indian off." For a little boy especially, that's as horrible a story as you ever want to hear.

We've done that to almost every culture in this country. Everyone's expected to assimilate into this little box.

Yeah. People don't like "different." I guess native people from all countries who were invaded by Europeans, had a horrible experience. There's this place I really love called Acoma in New Mexico. Acoma is the name of the tribe and is one of the oldest civilizations in North America, over a thousand years old. They live on top of this huge mesa in the desert. The original buildings from over a thousand years ago are still there, and are still lived in. There's a church up there that was built when the Spanish came. The Spanish made these Indians into slaves, and used to make these Indians run relay-style, with these logs that they had to get dozens of miles away, in order to build this church. So they had this reminder there. And some were affected by Christianity. And there's a place there that's sort of in between both worlds. The peyote religion is some of that, too. They think Jesus was a good guy. Here was a guy just trying to do his best to fight against oppression. But you look at that church, and just think, "God, how cruel," even though it's a beautiful structure.

When you reached your teens, had you begun to pull away from the Indian world?

It wasn't a pulling away. I was from this city environment. My mother didn't want me to have to grow up the way she did. I had this key to go inside these two worlds freely, with no one to check my passport. That was a wonderful gift. When I was very young, in my mind, I thought the cool action was on the reservation, because you were connected to outside, to a freedom. Your playground was the world, it felt like to me. In the city you were confined to a back yard. I didn't have any brothers or sisters. On the reservation, I had hundreds of them. Plus they were amazingly in touch with nature, in ways that never happened in the city. They'd take you out into this lush field and find this one little plant and pull it up, and yank this thing from the bottom and taste it, and it tasted more wonderful than anything you'd find in the city! It was amazing. They could all do shit that nobody else could do!

How did you get back into Native American music again?

It's one of those things that just creeps into your consciousness and creeps into your soul, and you don't have a reason why except that it's in the air, and it's part of this unknown magical thing in life that you're really thankful for, that these gifts come along. It isn't a calculated move. It isn't clever. It isn't intellectual. It's just something that comes from its own place. In music in general, a lot that you count on is based on accidents and discoveries that you trip over that leads you to do something you never would have been able to calculate and figure out. It's also something to do with the fact that parts of you that (are left behind) are almost always going to come back and want to be acknowledged.

It sounds like you were always drawn to music, from the time you were a kid, at a very deep, "soul" level.

That was due to these people on Six Nations. I was in a lot of bands growing up, many of whom were made up of people who were just sort of (playing around). It was never that way for me. From my earliest memories there was music behind me, music in front of me, music was a part of the celebration of these people being together. It got ingrained in me. When I reached puberty and rock and roll came along at the same time and these relatives of mine are already teaching me to play guitar, it was perfect timing! Then when I met Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks, there was something about what they did that really pushed some buttons in me. There was a violence, an anger, a power...there was something that wasn't just happy-go-lucky (sings)"We're gonna rock around the clock tonight..." It wasn't like that. There was something mean and demonic and the music was like people really trying to play some shit and play it harder and faster than it had ever been done before!

Do you see the doors opening a little further to Native American culture in the coming millennium?

That's what something like this film is all about. I'm in the position to help out a little bit and say "There's something here in your own back yard that you don't really know that much about that happens to be the original roots music of North America. It happens to be something that's really quite beautiful and magical and for a long time it was your job to ignore it, but now I'm going to turn you on to it, but not in a stereotypical way. This is not the clichés you've seen in the movies. I'm going to do it the way I know people in the Native community hear it. This isn't about 200 years ago, or how it was 100 years ago, this is about right now. It's how we feel today. It's not over. It's not dead. It's not extinct, close enough, but not gone." People are so inclined to think anything to do with Native North America as yesterday's news. "Oh, that was beautiful. Those people, they used to be so wonderful 200 years ago." It's kind of a disregard for now. So I thought it was really important to say "No, no, no! We're makin' a noise right now, right today!"

No comments:

Post a Comment