In 1988, a young USC screenwriting student named John Singleton, who was already scripting his 1991 feature BOYZ N THE HOOD, had a few things to say at a Question and Answer session for the ages.

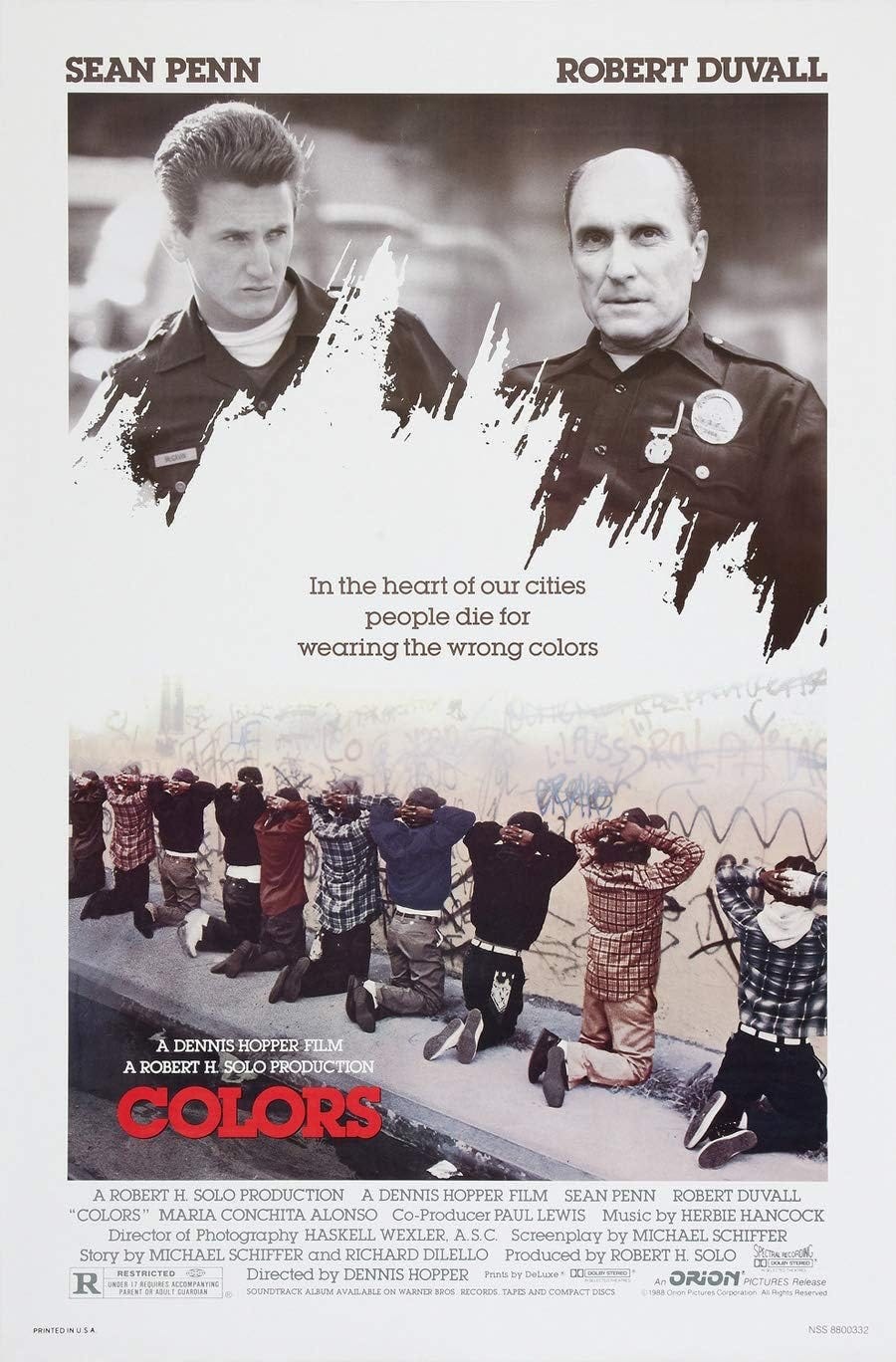

(COLORS was released theatrically in the United States 37 years ago this week, in April 1988.)

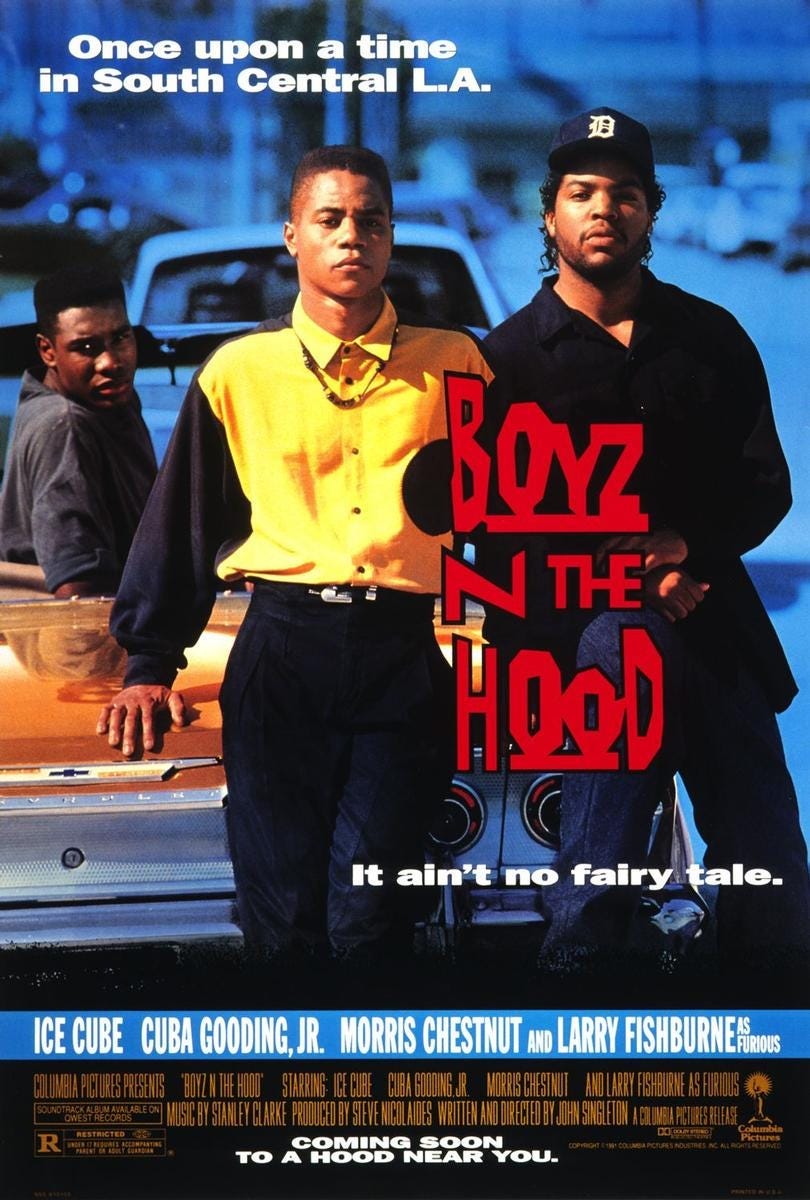

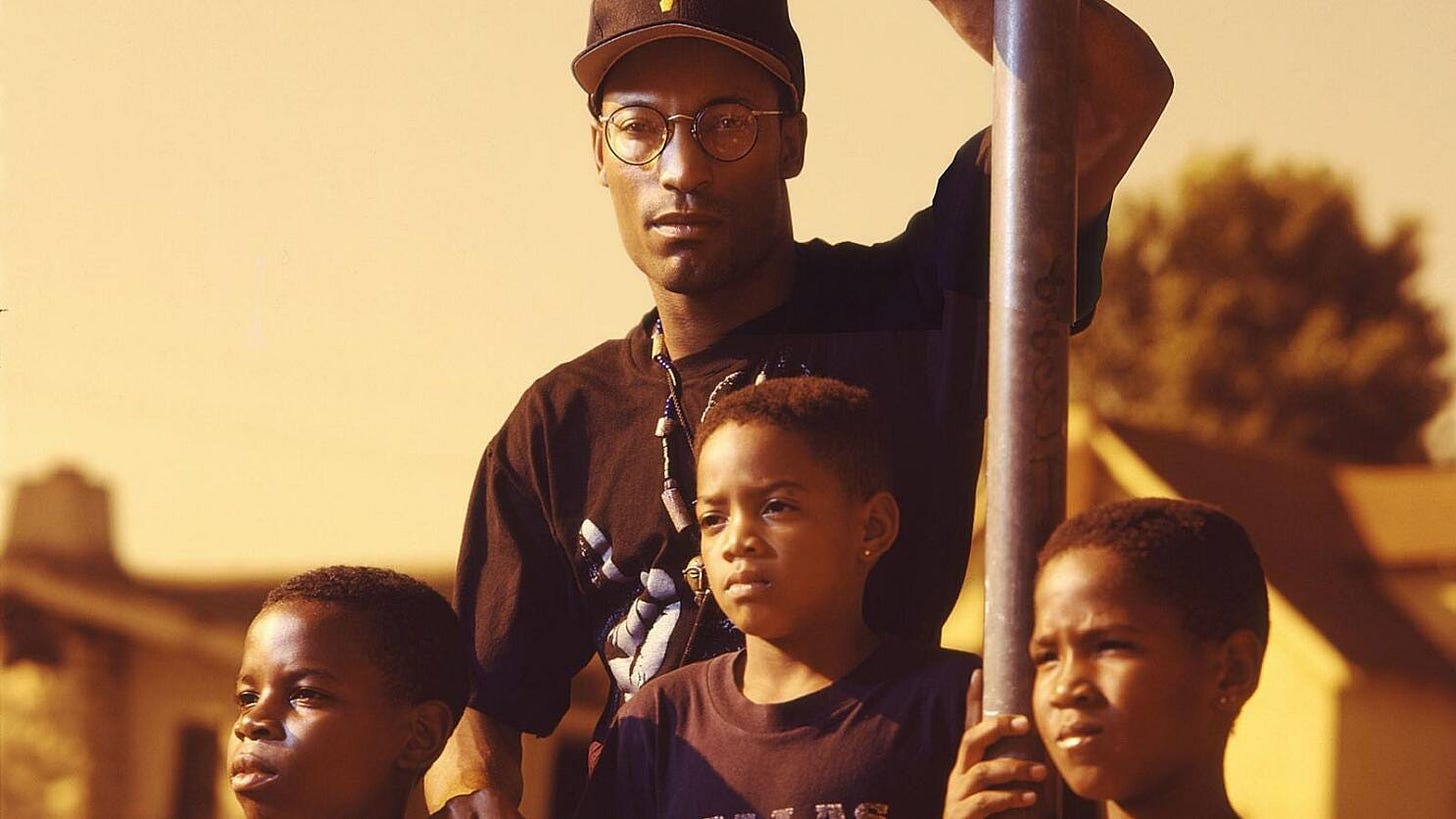

(A one-sheet for the 1991 release of Boyz n the Hood, above.)

“Your movie gets it all wrong!” shouted a male voice from the audience.

Our little group of Freshman Film Students, the average age being 18, sitting together at Norris Theater at the University of Southern California, all looked at each other with surprise and a little nervous laughter. Did somebody really just say that? Did a crazy person wander in off the street? There was no shortage of them in our university neighborhood.

“Your movie gets it all wrong!” was just not the typical response heard from students at the class known as 466 at the University of Southern California’s Film School, then more formerly called the USC School of Cinema-Television, and today dubbed the USC School of Cinematic Arts. 466 was held weekly on Thursday evenings at Norris Theater, and featured a screening of a soon-to-be-released theatrical feature, followed by a Q&A with a luminary from the film. During the past two semesters, the collected grad and undergrad and faculty of USC Film School had held court with the likes of Leonard Nimoy, William Friedkin, Ridley Scott, Edward James Olmos, and Martin Sheen, all of whom answered our very reverent queries.

A particular highlight of the prior Fall semester was when director Phil Joanou brought his debut feature Three O’Clock High, a “High Noon in a high school” comedy, to 466. Joanou had graduated from USC just two years before and progressed right to directing two episodes of the NBC series “Steven Spielberg’s Amazing Stories,” after Spielberg had seen a VHS of Joanou’s student thesis film, known at the school as a “480,” in reference to the class with the same number. The 480 thesis film was entitled “Last Chance Dance.” For his second feature, Joanou was directing what was known then only as “the U2 Movie,” and which would be released theatrically about a year later as the documentary “Rattle and Hum.” 1987 was the year of The Joshua Tree album, and no one was cooler than U2 amongst, well, a lot of us at USC, although the band had its share of haters even then. Joanou was even sporting a long hairstyle very reminiscent of Bono at the time, making him look a bit like a fifth member of the group.

Joanou had been part of the undergraduate production program, like my friends and I, which was considerably smaller than the similar graduate sequence. At the time, undergrads were rarely given the opportunity to direct one of the coveted 480 films in the first place, as more resources were allocated for the graduate students back then. However, Joanou had not only directed a 480, he had also catapulted into the “industry” to great success on the back of that 480. Just a few years older than us, Joanou was someone we could aspire to be. Even cooler than the association with U2 was that Joanou had received the tap on the shoulder from none other than Spielberg, whose legend, along with that of George Lucas, loomed over USC Film School like dual colossuses. Steven Spielberg, had famously been rejected from USC Film School, and attended Long Beach State, but he had joined with actual alumnus Lucas in donating buildings to the newly renovated Film School in 1984. Their respective names stared at us as we headed to class each day. (To be clear, there were plenty of my fellow film students who were also inspired to become filmmakers by so many other directors. Names like Friedkin, Scorsese, Lynch, Truffaut, Hitchcock, to name just a few. That being said, the legends of Spielberg and Lucas were inescapable around the Film School.)

Joanou’s seemingly overnight success had been the focus of short articles and blurbs in the mainstream movie publication Premiere, an article in New York Magazine, and one in the Los Angeles Times, amongst many others. In a stall of the men’s bathroom at Norris, someone had scrawled on the wall, with a pen, “Phil Joanou shat here.” When you’re the subject of a scatalogical-graffiti tribute at your film school alma mater, you have definitely arrived.

Some members of our undergrad class, totaling about 15, swarmed Joanou after the Q&A. The returning hero was happy to answer any of our questions, very warmly, even giving us each his business card, from the office he now kept at Steven Spielberg’s company, Amblin Entertainment. The card featured a silhouette of E.T. and Elliot flying through the air on the bicycle. The reverent manner in which some of the starstruck gang, including myself, held those business cards after receiving them, you would have thought they were Willie Wonka’s Golden Tickets.

Many of the bigger name guests would be ushered out a back door shortly after the Q&A ended, but Joanou stayed to speak to as many students as wanted to speak with him. When the faculty indicated that they needed to close the theater, the conversations with Joanou continued outside Norris. By around 10 PM, Joanou intimated that he needed to be getting home, but that we could keep talking on the way to his car, which was parked a few blocks away on campus. We then followed Joanou in a film student parade of sorts, until he got into his vintage Porsche, but not before graciously wishing us each good luck on our own 480s. I never got selected to direct a 480 myself, a few years later, when I was an eligible senior, but it was a nice sentiment from him. Getting the director slot on one of those 480s could be a real-life Golden Ticket at USC Film School, as it had been for Joanou.

Joanou’s vintage Porsche made a noticeable clunking sound as it pulled away, and one of our group remarked, in reference to the car that didn’t sound like it might even make it to the nearby 10 Freeway, “He probably just hasn’t gotten the residuals from Three O’Clock High yet.” We regularly threw around words like “residuals” as if we knew of what we spoke. A few of us even subscribed to Daily Variety. I myself would keep that Amblin card in my wallet for the next six months, dragging it out at college parties in ridiculous fashion to tell the story of my “friend Phil” who worked for Steven Spielberg. What I should have done was try actually calling him to see if he needed an intern, but I had placed him on a pedestal in my mind and was intimidated to make that call.

The 466 Guests were mythical figures, of different stripes, that descended upon our campus each week. Some, like Joanou, were close enough to us in age that we could imagine ourselves being them. Others were titans, such as Nimoy, who we had grown up with on the small and big screen, and just being in the same room with them was a thrill.

We never thought someone from the school would ever challenge one of the 466 guests, but that was on the menu this particular Thursday. Colors was released theatrically on April 15, 1988, so the date of this 466 class would have likely been one of two Thursdays before the official release, that being either April 7, or April 14, 1988.

The guest at 466 was sometimes the star, sometimes the director, sometimes the writer(s), and on a slower night, we’d get the producer.

The evening Colors screened at 466 was supposed to be a slower night.

Colors starred Robert Duvall and Sean Penn, and was directed by Dennis Hopper, but none of them would be in attendance. The primary producer, Robert H. Solo from Orion Pictures, would be doing the Q&A.

Orion likely saw Colors as their typical mid-level spring/early summer release, the type they had mastered: a medium studio film budget (in this case, somewhere between 6–10 million), with stars who were nonetheless not too big to afford, and a familiar genre structure, in this case a buddy cop story, which Orion was known for putting some unique twists on.

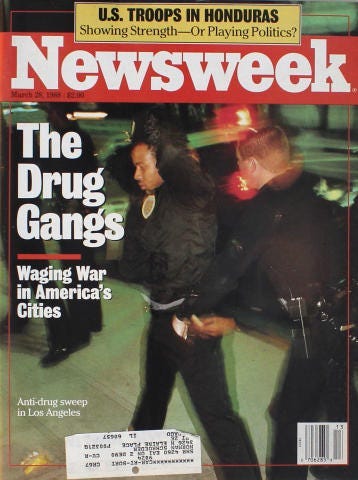

The unique twist in Colors was that its more familiar story of two cops learning to get along and survive had been set against a backdrop of the street gangs of Los Angeles, a subject that had relatively recently put the wars between the Bloods and the Crips on the national radar via various media and news outlets. A recent example was the March 28, 1988 cover of Newsweek, with the headline “The Drug Gangs” and a photo of an African-American gang member being arrested in Los Angeles. The 80s were a period of American life when being featured on the cover of either Newsweek or Time meant that story was amongst the big news of the week, seen at every supermarket check-out counter. Recaps of the big cover stories were also often on every national and local news station. A nationwide fascination had sprung up over the concept of rival gangs who each wore a distinctive color, red in the case of the Bloods, and blue for the Crips. Also catching media and public interest was the concept of “drive-by shootings” between the adversaries, which felt like a uniquely California car culture spin on gang warfare.

Before opening the doors at Norris Theater for a 466 screening, students would gather outside, sometimes over an hour before showtime. On the evening of the Colors screening, there was a bigger crowd waiting than I had yet seen at 466. There was no way everyone was going to get a seat.

Publicity of all kinds was trailing Colors before its imminent opening, which helped to make this campus showing such an event. Orion had recently screened the film to a few sets of young audiences in Los Angeles, and in one instance, some Los Angeles gang members got into a fist fight, but not much more detail was reported in the news than that. The Guardian Angels, who had recently increased their presence in L.A., predicted that there would be gang violence in theaters when Colors was released, and the NAACP denounced Colors in advance for glorifying gang violence. This was before most people could have ever seen the film, which we were all about to in Norris Theater.

While any USC students were allowed to attend 466 screenings, actual Film School majors got first crack at the seats in Norris Theater. For those nights, we were the envy of the students who lined up in the “other” queue, hoping to get into a few of the empty seats held for non-film students. During a period of time when the “geek with a camera” was a ubiquitous, but not very heroic, character in 80s movies, 466 was a nice perk for we geeks with cameras.

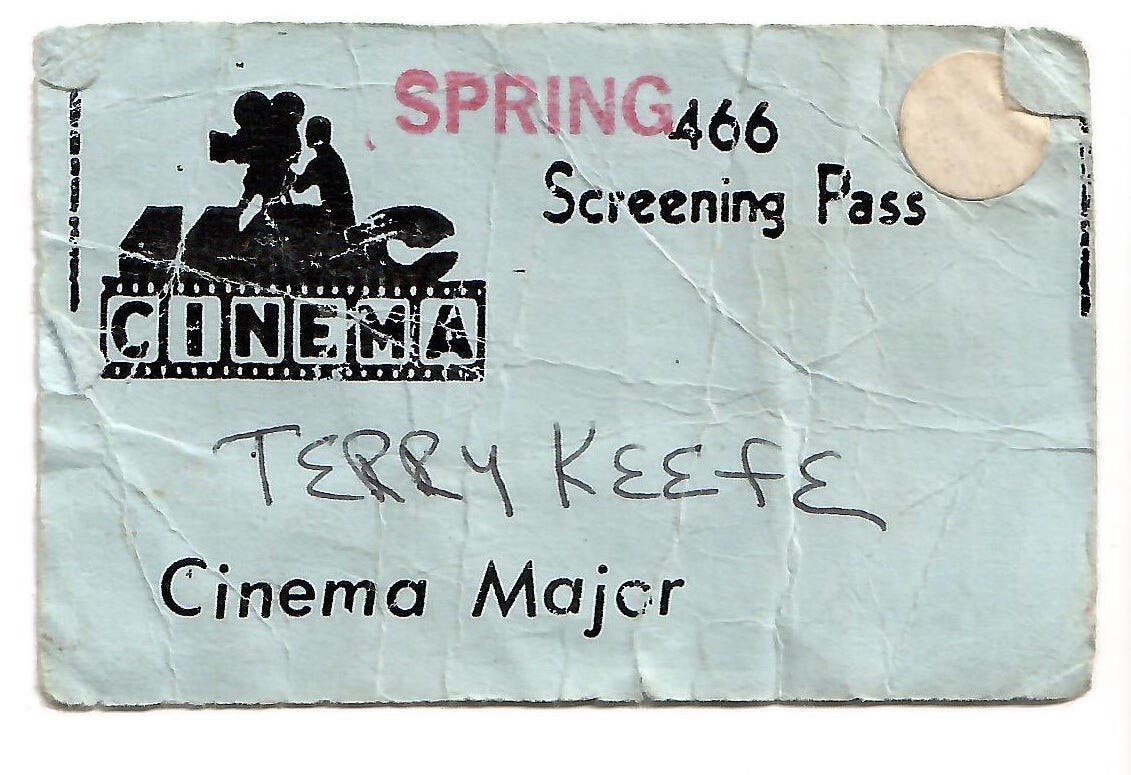

Each of us even had a special 466 card, with the USC Cinema-Television logo emblazoned on it, which you would hand in upon entering Norris. There was a color-coded system used with the cards, with a red dot on the card being for full film majors, and a blue dot being for minors. After the screening and Q&A was over, a teaching assistant would call off the names of everyone to come pick up their cards one-by-one. Every time, during the years of 1987 and 1988, mild chuckles would erupt when the name of a student, “Steve Spielberg,” who was a tall jock type, was called. This particular Spielberg, who I think was a cinema minor and presumably was unrelated to the famed filmmaker, seemed annoyed by the laughs every time. In comparison, there was always a grad student, whose name I never knew, at most of the 466 screenings who had clearly styled his look after late 80s Spielberg, with the shaggy hair parted the same, similar beard, and even the same circular glasses often worn by the director back then. He stood off to the side when Phil Joanou was speaking to all of the rest of us post-Three O’Clock High screening, and just sort of stared at him, as if he were waiting for Joanou to acknowledge that he was cosplaying his mentor. That guy would have loved to have a 466 card with “Steve Spielberg” on it.

Colors was even attracting students you never saw anywhere near the Film School, unless they were lost. Such as a large group of enormous USC Football Players, who were banging on the doors, having arrived late, and pushing to get into the sold-out screening after everyone had already been seated. Football Players were kings on the USC campus in that era. I had recently experienced the entitlement of one gridiron star who kept dropping a “cheat sheet” over his shoulder, onto my desk, asking for the answers to specific questions, during an Earth Science 101 final. I barely knew this guy and there was no way in hell I was doing that for him. It didn’t matter, because the sorority girl next to him was willing to help the poor lad pass and scribbled a few granite/quartz-related answers back to him. Versions of that incident played out all over campus on a daily basis. So, it gave me some pleasure when the 466 teaching assistant explained to the gang of Players that the screening was totally sold-out. Some of them couldn’t believe it and acted like they had never been turned down for anything on the USC campus before. I heard one of them actually say the position he played, as if that mattered much at the film school. Get in line, jock-o.

There had been rumors that Dennis Hopper would make a surprise appearance that night at 466 also — “They’re hoping he can come,” said a teaching assistant in the know earlier that day — but it wasn’t to be. Hopper was something of an unexpected choice as director for Colors, only his fourth feature at the helm since Easy Rider put him on the map as a filmmaker in 1969, a map which he was nearly removed from with his financially and critically disastrous second directorial effort, The Last Movie, in 1971. Hopper hadn’t directed a feature since his little-seen 1980 film Out of the Blue, but he was currently in the middle of an acting renaissance, and surge of popularity, with his role as Frank Booth in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, Feck in River’s Edge, and as Shooter Fletch in the commercial hit Hoosiers, all released two years prior in 1986.

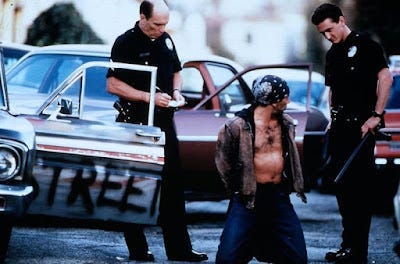

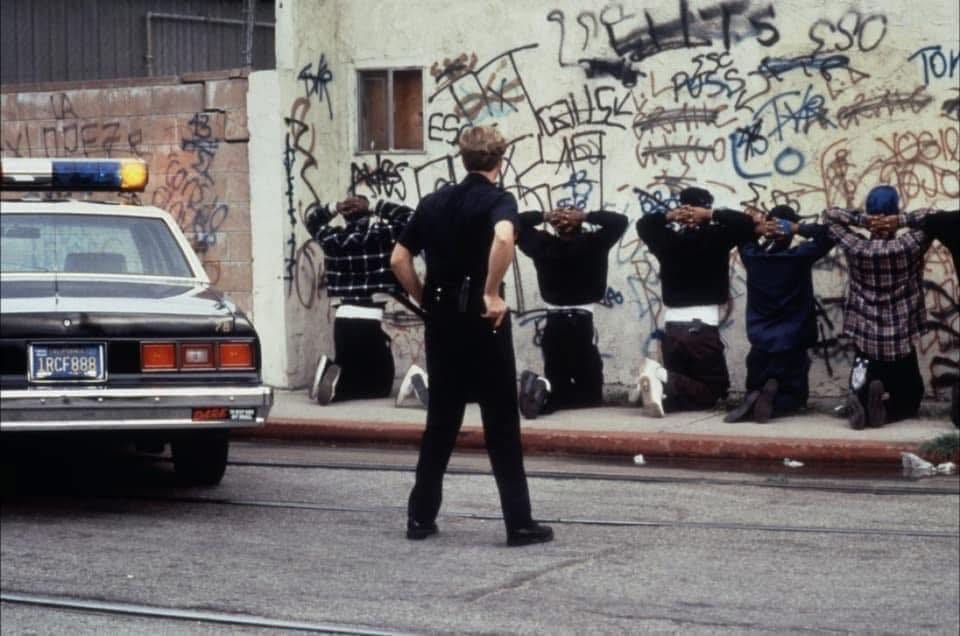

When the lights came up in Norris, after Colors had screened, the applause from the assembled film students was more polite than enthusiastic. Colors is set in the LAPD’s then-real life, and now defunct, C.R.A.S.H. Unit (which stood for Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums) in which the brash young rookie McGavin (Penn) learns how to police the gang neighborhoods under the wiser tutelage of C.R.A.S.H. veteran Hodges (Duvall). The plot is driven by a search for a shipment of drugs and money that threatens to trigger a larger gang war. I shared what seemed to be the audience’s very middle of the road reaction and felt that Colors was a solid cop film, but there was something missing that I couldn’t articulate. My movie analysis skills were still pretty nascent at that point, although I also had to admit the film cast a grim spell that had left me feeling gut-punched.

As the curtains closed and two chairs were put out on stage for the Q&A to come, the Moderator for the evening introduced producer Robert H. Solo, who took one of the seats. The Moderator was either Charles Champlin, revered Los Angeles Times film critic, or Rick Jewell, a professor in the USC Critical Studies Department, as one of the two of them handled almost all of the 466 Q&A’s that year. However, my own memory fails as to which one handled that night, and none of the half-dozen former classmates I’ve asked seem to recall either.

Whether it was Champlin or Jewell, the Moderator would soon have their hands full.

In his late 50s, Solo was dressed in a sports coat and slacks. After beginning his career as a studio executive, Solo had previously produced the legendary Ken Russell’s The Devils in 1971, and later, the terrific 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, as well as 1983’s Bad Boys, no relation to the 1995 Will Smith-Martin Lawrence film of the same name, but a teens-in-prison flick starring a young Sean Penn, Esai Morales, Ally Sheedy, and Clancy Brown. Directed by Rick Rosenthal, Bad Boys was a ubiquitous presence in video stores large and small at the beginning of the video rental boom. The early drafts for Colors were set in Chicago, where Bad Boys had been filmed, and Solo mentioned in later interviews that Bad Boys was a catalyst for his interest in the world of gangs.

Presumably, Bad Boys was also the beginning of Solo’s working relationship with Sean Penn, who developed the Colorsscript with Solo, through a series of drafts with screenwriters Michael Schiffer, and Richard Di Lello, who share story credit, with Schiffer receiving screenplay credit. Most 1980s studio producers weren’t as prolific as the likes of Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, with a film or two coming out every year. Many spent years developing numerous projects, with the hope of getting one of them to a theatrical feature release. The studio producer was often the one who even came up with the general idea of a script in the first place, then hired a writer to “take a crack at it.” Feature film projects could then germinate for years at the major studios, until an attachment of a star actor or director helped launch a script off a shelf and into production. Even with a coveted studio “First Look Deal,” as Solo had at Orion Pictures, a feature film release was a rare occasion that came around once every few years, if the producer was lucky. In other words, this was a very big week for Robert H. Solo.

The Moderator pointed to an up-stretched hand in the audience for the first question.

“What was the above the line and below the line budget for the film?”

Light groans from the audience, as this exact question was asked without fail every 466 Q&A, and was usually posed by a student in the Peter Stark Producing Program, a graduate sequence which trained students in the business side of Hollywood and, specifically, in producing. Classes were often taught by top Hollywood producers, studio executives, and talent agents. Known as “Starkies” within the film school, many of the Peter Stark students wore suits to class, and some also carried briefcases. For we “young artists” in the undergrad production and writing programs, these Suits-in-Training were exactly what we had majored in film to not become. Little did we know that some of these same people are who we would be pitching for funds in a few years, but that was still far from our willfully naive minds. “Never selling out” was a big mantra of our generation of artists in general, although many of us would be absolutely dying to sell out not long after graduation when we actually had to make a living of some sort.

Solo answered the above the line/below the line query with very specific figures, which got a bit of a laugh because really only the producer would usually have that information down to a dollar, based on past guest responses to the question at least. Sometimes the director wouldn’t even know the breakdown of the budget, an actor usually not, and a writer almost definitely not, although they would often reply with something like “Well, I can tell you what I was paid.” But a Starkie still asked the question every time, no matter who the guest was, and likely, the query was an outgrowth of a production budgeting class some of them were taking.

The next question wasn’t really a query at all, but more of a definitive statement.

“Your movie gets it all wrong!!”

A Young African-American Man of approximately 19 was standing up and gesturing at Solo from about three rows back. He was thin, wore glasses, and had been sitting with a group of male and female friends, who were watching him intently. All of the rest of us were now watching him intently as well, as in basically the entire assembled Film School.

We had never heard anyone tell one of the 466 guests that they didn’t like their film, much less whatever the hell was happening here.

“I grew up in South Central! My mother kept me out of gangs, this isn’t what it’s like at all! This movie gets it all wrong!”

The Young Man went on to attack Colors for being marketed as a “realistic” portrayal of Los Angeles gangs, but which was told from the perspective of two white cops. He then specifically went after scenes he thought were unrealistic. First, a scene in which an African-American couple are naked and energetically having sex, when the LAPD bursts in and shoots the man dead, as he was reaching for his pants. The Young Man argued that the police would have let him get his pants on. He next pointed out another scene, in which the police raid a drug house and bring out a woman handcuffed, and totally nude. The Young Man pointed out that the police would have let her get dressed first. I had to agree that the graphic nudity in both of those scenes felt straight out of an exploitation film and these criticisms were spot-on.

A hush in the audience. Nervous laughter, and a few coughs. Then, the most uncomfortable silence for what felt like half a minute or more. Finally, Robert Solo responded.

“We hired members of the C.R.A.S.H. unit as consultants. We had actual gang members as some of the actors,” said Solo, and added, “Ice-T wrote the theme song.”

“Well, Ice-T didn’t write the script!” the Young Man shouted back, which got a round of laughs from the audience. The Young Man then sat down. A murmur in the crowd slowly settled.

“Thank you for your comments,” the Moderator said to the Young Man, then turned back to Solo, “So, how did you start working with Dennis Hopper?”

“Dennis came in for the meeting wearing all these crazy clothes…” started Solo.

This got a laugh from an audience that needed to put the tension somewhere. Crazy Dennis Hopper stories are always a crowd pleaser anyway, and Solo then dived into how Dennis went about casting.

The rest of the Q&A was pretty much status quo, with questions about script development and financing. But, when my friends and I returned to what was known as “The Cinema Floor” at the dorms of Birnkrant Hall, as most of the residents were film students of some sort on the 4th Floor, we only had one question: Who was the Young Man?!

A friend who was in the screenwriting program, known formally then as the Filmic Writing Program, told us that the Young Man was named John Singleton, and that he was also in the Filmic Writing Program, but a year ahead of us. Other than perhaps large lectures, I wouldn’t have had any classes with Singleton up until that point.

“That guy’s never gonna make it in Hollywood!” declared one of our group. Obviously, this particular statement deserves a gold trophy for Worst USC Film School Career Prediction Ever, to be shared with whatever hapless administrator rejected Steven Spielberg’s application in the 1960s. However, we all did agree that getting up and shouting at a 466 guest just felt like a recipe for career destruction. It also needs to be stated that the undergraduate film programs at USC at the time were composed overwhelmingly of white students. The group of friends I’m referring to in this piece were all also white, and male. While I can’t imagine any us reacting to Colors with the public anger that Singleton did, our life experiences up until that point were also likely very different than his.

Something else was new to me, though, in watching and hearing what Singleton said that night: he was more passionate in how he felt about a film, negatively in the case of Colors, than I had ever been about any piece of art that I had seen up until then. And man, the pure guts he had at that age. He was the first film student I had ever seen stand up publicly and say a film made by the major studios simply didn’t work, directly to a representative of one of those major studios. There was something daring and freeing in how he expressed this that I had not encountered before. You could tell the powers that be of Hollywood when their films were terrible.

In his comments at 466, Singleton also nailed on the head what was bothering me about Colors but which I couldn’t put into critical words at 18. Specifically, that Colors makes only a minor effort to develop most of the gang members, effectively the bad guys in this story, as characters. One notable exception is a somewhat older Latino gang member named Frog, played by the late Trinidad Silva, who anchors a few key scenes that contain explanations as to why some young men are attracted to join gangs. (Silva, tragically, would pass away just a few months after the release of Colors, in July of 1988.) While boasting notable supporting talent like a young Don Cheadle as the effective main villain, a drug-dealing gang member named Rocket, most of the gang members are there essentially as blank foils to the police characters, playing their part as antagonists to the cops in car chases, shootings, and interrogations, but little beyond that.

Within a few weeks, Colors became both a box office success, grossing 46 million, and a major source of controversy. Violence between gangs in Los Angeles did break out at movie theaters showing Colors, and there was also one gang-related shooting outside of a theater in Stockton, California that was screening the film. Across the country, many theaters opted not to book the movie at all, in fear of more potential bloodshed.

The real-life LAPD and Colors were also blending together in April 1988, as the actual C.R.A.S.H. unit of the LAPD was involved in something called Operation Hammer, where numerous gang members were arrested, that same month. The arrests of Operation Hammer peaked approximately one week before the release of Colors when, according to Wikipedia, “1,453 people were arrested by one thousand police officers in a single weekend.” However, this huge sweep of arrests only resulted in 32 charges being actually filed, making it look far more like a PR stunt for the LAPD in retrospect. Many news pieces about Operation Hammer also found a way to mention Colors in the spring of 1988, perpetually intertwining the film and the topic of L.A. gangs.

In writing this remembrance, it was helpful to examine how Colors has been viewed over the subsequent decades, just as much as how it was perceived at the time of release. Said film writer Santino J. Rivera on Poco.com in a 2013 article entitled “Everything You Wanted to Know About Colors, but Were Afraid to Ask,” “Say what you want, but it’s an important film and one that displays a change in attitude in Hollywood towards people of color. It wasn’t too long before Colors came out that Hollywood was portraying us as break dancers and pesky neighborhood kids. Dennis Hopper changed all of that and things have never been the same.”

Dennis Hopper was quoted as saying, in defense of Colors on NBC’s “Today,” “I know that Abraham Lincoln was shot in a theater, but I don’t think it’s because of the play he was seeing. I’m merely pointing my finger at a problem and saying there’s a major problem in Los Angeles. It’s a crack problem, and it’s a problem that kids are killing each other. And it’s not a movie problem. The movie can only say, ‘Look, this is happening.’”

Producer Solo added in an interview with Bobby Wygant, “Colors is not a message picture. It’s a portrait. It’s letting the public know, who had blinders on, what is going on in our cities. What are we going to do about it?”

Hopper and Solo were correct in that the film did help shed light on the gang problem in L.A., which many in other parts of the country and the world would have not known about otherwise. A buddy cop film structure also helped provide something familiar to hang onto for an audience that might not have interest in seeing a film set just within the gangs themselves, or so the conventional wisdom likely went at the time. Without what Orion perceived as commercial hooks, i.e. two white movie star leads, it was also very possible that a film about the gangs of Los Angeles was never touched by a major studio at all in 1988. Although, that perspective was about to change.

If Colors didn’t satisfy everyone as the ideal film on Los Angeles gangs at the time it was released, another, very different, film set amongst the gangs of Los Angeles was right on the horizon. Word spread quickly on campus in spring of 1990 that a USC student had just made a major deal with Columbia Pictures to write and direct a feature film. A specific name wasn’t attached to the verbal telegraph that got the news around the school, but soon, it would be.

The USC filmmaker’s name was John Singleton.

The upcoming film, entitled Boyz n the Hood, and reportedly about a group of three friends growing up in South Central, was scheduled to go into production in the fall of 1990. A friend recalled that Singleton stated in a later interview that he had been inspired to write Boyz after the 466 Colors screening, but I have never been able to actually find that interview. It also doesn’t jibe with a number of things that Singleton said in interviews about the creation of the screenplay, which he has said really started germinating back when he was a kid sitting on his family’s porch and watching things that went on in the neighborhood. He also explained that he had submitted a synopsis of what would become the Boyz script with his freshman admission application, along with a few other ideas.

Singleton would later recollect in interviews that he wrote much of Boyz in the USC Computer Lab, because he didn’t have a computer of his own. The late 80s were a time when maybe 1 out of every 8 or so USC students owned a computer. To meet the demand, the Computer Lab, located in what was a large windowless room, was filled with Macs that any student could use, was often open very late, and was packed with students during exam time, when term papers were often also due. Singleton would also recall that he wrote Boyz at the Lab using Microsoft Word, as screenwriting computer programs had not come into fashion yet. He would submit a finished draft of Boyz as his senior thesis, and he graduated from USC in May 1990, effectively already a studio director. While many of the rest of us at the Film School were clamoring to get picked to direct a 480 project, and then hope it turned out good enough to get industry attention, so we could maybe get hired to direct, or have a lunch meeting with a development executive at least… John Singleton had barreled through all of that and kicked down enough doors to get right to the major studios.

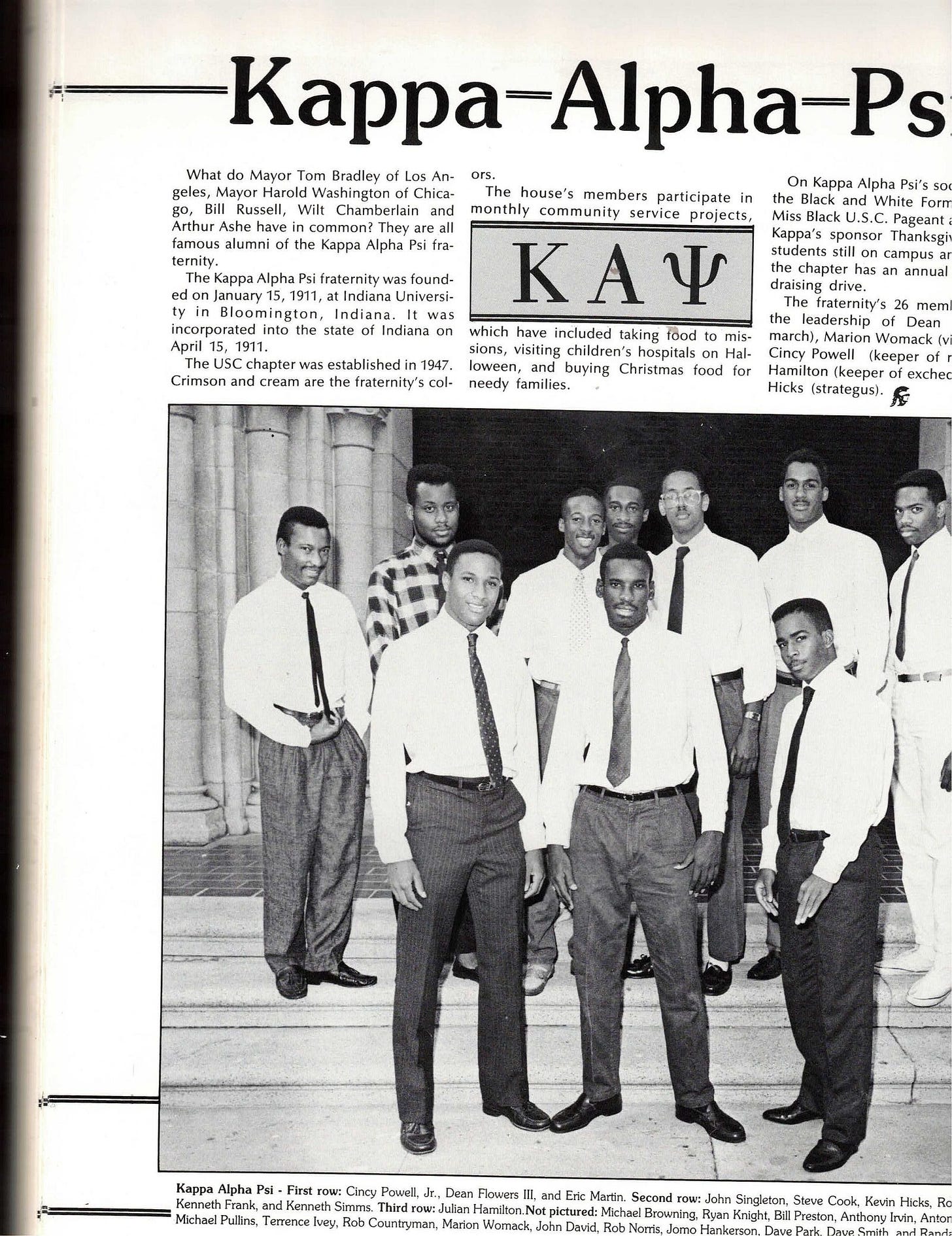

(Above, the only college picture I’ve been able to find of John Singleton was in the 1988 USC official yearbook, EL RODEO, which featured Singleton as part of the group picture for the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity. He is first on the left, second row. Credits: EL RODEO Yearbook)

In May 1991, Boyz n the Hood premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, to rapturous audiences and great reviews. Released theatrically a few months later in July, Boyz became a box office hit globally, sweeping like wildfire around the world, and heralding the arrival of an exciting new filmmaking voice.

As the two major studio films centering around Los Angeles gangs produced up until that point, Boyz n the Hood and Colors would quickly be compared by critics and audiences. While there were numerous obvious similarities between the two films due to subject matter and setting, the differences in tone and POV are stark from the opening title cards.

Colors begins with an ominous scroll which reads:

“The Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department each has a gang crime division. The Police Department’s division is called C.R.A.S.H. (Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums) and the Sheriff’s division is called O.S.S. (Operation Safe Streets). The combined anti-gang task force numbers 250 men and women. In the Greater Los Angeles area, there are over 600 street gangs with almost 70,000 members. Last year there were over 387 gang-related killings”

Whereas Boyz begins with a single title card with this message:

Boyz: “One out of every twenty-one black Americans will be murdered in their lifetime. Most will die at the hands of another black male.”

Boyz star Ice Cube directly referenced Colors, in an interview in 2011 for the documentary The Enduring Significance of Boyz n the Hood, “Colors is one thing, this ain’t it. This isn’t a movie telling you how bad it is to be a cop. This is a movie telling you how bad it is to be in the hood.”

Ice Cube’s seminal group N.W.A. was formed in 1987 in Compton, not far from the USC neighborhood, and their legendary album Straight Outta Compton was released in January 1989, likely recorded around the same time as the release of Colors. “Boyz-n-the-Hood,” which Singleton borrowed his film’s title from, was the album’s first single. Singleton later told a story that he had first met Ice Cube while Singleton was college interning on “The Arsenio Hall Show,” and then again at a concert in 1990, after the Boyz script had sold. Singleton pitched Ice Cube on starring in the upcoming film that night, but then also had to ask Cube for a ride back to his dorm at USC.

The sounds of a Colors-like shootout, with gunfire, helicopters, and sirens, play out behind the opening title cards of Boyz, but the sound design isn’t used to introduce us to the neighborhood in the middle of a police action. Instead, it helps set up the world that the three adolescent versions of our main characters — named Tre, Doughboy, and Ricky — live in every day. We meet the kids as characters, and, specifically, our lead characters, in a marked difference to Colors, where the first residents of South Central that we meet are nameless gangsters wielding guns and being chased by police. The film then cuts ahead to introduce us to the 17–18 years old Tre (Cuba Gooding, Jr.), Doughboy (Ice Cube), and Ricky (Morris Chesnut), who have since grown to near-adulthood in South Central, and are each on very potentially different life paths.

Something that distinguished Boyz for me immediately, not just from Colors but from most mainstream entertainment of the time, was that it was the first studio film that felt like it had been made from someone in my generation, as there were references and statements about cultural norms which had rarely appeared onscreen until now. The young characters mention AIDS, which might as well have not existed in Movieland, for as many times as studio features even acknowledged the illness, but it was what my generation seemed to spend half its time time thinking and talking about. They also discuss the related use of condoms, a similar conversation to which my friends and I may have had countless times back then, but which rarely was echoed in films. Larry Fishburne’s character of “Furious” Styles, Tre’s father, refers to the SAT test as “culturally biased,” something that many were arguing to be true in the real world, but a statement which would also not likely pop up in the movies of the day. When the younger versions of the three friends find a dead body in an alleyway, they pass a bullet-ridden election poster for Reagan-Bush, a bit of negative commentary on the Reagan Years, a sentiment which also most definitely wasn’t seen often in mainstream Hollywood productions, but which was unavoidable in youth culture and on college campuses.

Boyz showcases strong acting performances throughout, including turns from Angela Bassett and Tyra Ferrell as the mothers of the lead boys, and Nia Long as Brandi. Fishburne as “Furious” Styles continues to dazzle on a recent rewatch decades later. Continuing the pattern of introducing ideas and concepts rarely seen in Hollywood films up until that point, Fishburne performs what is essentially a monologue about the dangers of gentrification, while visiting another part of South Central, with his son and friends, that is prophetic, and powerfully written and performed, with passages like, “It’s called gentrification. It’s what happens when the property value of a certain area is brought down. When they bring the property value down, they can buy the land at a lower price. Then, they move all the people out, raise the property value, and sell it at a profit. What we need to do, is we need to keep everything in our neighborhood, everything, black-owned, with black money.”

In comparison to the end of Colors, where Sean Penn’s McGavin has learned to control himself a bit and is trying to educate his own new hot-headed young partner, the tag at the very end of the credits in Boyz is simply “Increase the Peace.” Boyz has a very different point than Colors, the latter of which seems to be a truly hopeless one: that there is no way out of the cycle of violence of the gangs. Ice-T essentially voiced the film’s conclusion himself on the soundtrack: “The gangs in L.A. will never die — just multiply.”

Despite the emotional devastation left by the shooting of a main character at the end of Boyz, there is hope for the future as the film draws to a close, but certainly, no easy answers are provided. Tre looks to have a good chance at a better tomorrow, but it also involves him leaving South Central to go to college far away at Morehouse.

Similar to events that happened upon the release of Colors, there was also gang-related violence at theaters showing Boyz n the Hood. Singleton defended his own film against accusations that it caused violence. Similar to what Hopper said three years prior, Singleton asserted, “I didn’t create the circumstances under which people shoot each other.”

Singleton, who was 23 at the time of the release of Boyz, would become the youngest filmmaker ever to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Director for Boyz, at 24, and the first African-American to ever compete in the category. He would also receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay.

When asked about his experiences at USC in a 1994 interview on “Late Night with Conan O’Brien,” Singleton explained some of the challenges he encountered as a person of color in an overwhelmingly white film program at the time, saying, “I got in the film program. And you know, I was one of like 14 African-Americans in a program that had like 2000 students. Since my success, they’ve admitted, like, you know, more than that. But I mean, when I was there, dudes used to look at me and be like, ‘Oh, well, you should just give it up, you know. Cause you’re black and you’ll never make it.’ After a while I was like, you know, I was trying to be cool with people. But I was like, ‘You know what? You know, kill this, you know?’ So I just stepped to everybody after that. And I was, like, listen, ‘I’m gonna make movies. You are not going to make movies. You have nothing to talk about, you know? I have life, you know, I have a life? You know, what do you have to talk about? You gonna talk about growing up in Encino?’”

Although Singleton was harsh in his recollection of some of his USC Film School interactions early in his career, he would eventually become an advisor to the school, appearing at numerous fundraising events, and speaking at the 2006 Commencement. Recalled USC School of Cinematic Arts Dean Elizabeth Daley in 2019, “John frequently showed up just to watch films with students, and would stick around long after the official end time of any program to speak with them about their projects. Importantly, he always brought students into the professional fold, hiring them on his films and television projects.” Daley, in should be noted, as instrumental in allowing more undergrads to direct the vital 480 projects, when she took over as Dean in 1991.

A screenwriter friend, who was also in attendance at the 466 screening as a student that night, encouraged me to give Colors a re-watch these many decades later, saying it was better than I remembered. He was right, and I found much more to respect on director Hopper’s part than I initially had, although I can’t say I enjoyed the film much more than I did as a college freshman. Colors remained a bleak ride for me, over three decades later, and, at times, an odd blend of tones and styles. Shot by legendary DP Haskell Wexler with the often verite feel he was famous for, the camerawork is loose and sometimes handheld, creating an atmosphere of constant danger, where it feels like something, or someone, is ready to explode at any moment, and often does. This is when Colors is at its best. But mixed with the verite style are big studio action set pieces, such as a wild car chase through the streets of Venice, accompanied by an action-driving Herbie Hancock score that could have appeared in numerous other cop films of the day. Cars explode, a shoot-out takes place in a fancy restaurant in which a gang member named High Top crashes through a plate glass restaurant window on a motorcycle, then takes a well-dressed white woman hostage. Yet another car chase through South Central ends in a car crash and explosion into the famous Watts Towers, with Penn and Duvall stuck upside down in their flipped squad car, exchanging buddy banter, which sets up the next scene in which Penn has dinner with Duvall and his wife.

One can feel director Hopper really straining against the conventional buddy structure, trying to expand the world of the film in the edges wherever he can, which results in a picture built around familiar tropes but also mixed with lengthy scenes completely apart from the cop characters, such as when a group of Latino gang members, led by Trinidad Silva’s Frog, initiate a younger member, through a beating and then a welcoming into their ranks. The scene serves as an examination of what draws young men into gangs, but it also feels somewhat shoehorned into the existing story structure, a sort of detour, although one that is welcome in that it is one of just a few scenes in Colors which tells things from the point of view of the gang members.

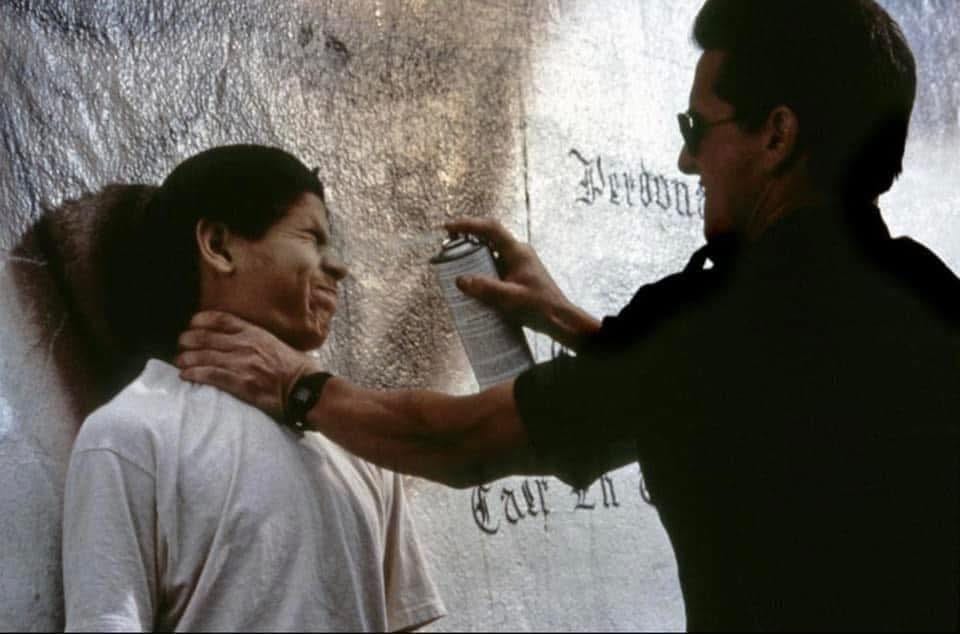

Colors also proved prophetic, in ways the filmmakers likely never intended. While ostensibly the hero of Colors, as he is the one of the two leads with a real character arc, Sean Penn’s McGavin can best be described as a bad cop. He spray-paints an adolescent graffiti tagger in the face. He punches a suspect, unprovoked. His attitude towards the gang members is pretty well summed up with his line, “I didn’t volunteer for C.R.A.S.H. to be nice and to play games with these assholes.” McGavin seems to become a slightly more restrained cop by the end, but he could just as easily be one of the cops caught on the videotape beating Rodney King a few years later as well. The same bad cops whose criminal trial acquittals in 1992 sparked the L.A. Riots, where parts of the neighborhood surrounding USC were looted and/or burned. I also couldn’t help but constantly be reminded of Detective Mark Fuhrman while watching Penn as McGavin, partially by his thug-like policing style, and also because of the manner in which he could rationalize it as a necessary part of the job. By 1994–95, Fuhrman would become the most famous LAPD officer in the world, because of his pivotal role in the O.J. Simpson Trial, in which the defense painted him as a racist due to audio recordings he made with an aspiring screenwriter, who was doing research about the police. Recordings in which Fuhrman used racial slurs repeatedly, and discussed graphic acts of LAPD brutality, including beating witnesses. The real-life C.R.A.S.H. unit, dramatized in Colors, would become the focus of the Rampart Scandal in the late 1990s and early 2000s, in which numerous LAPD officers were implicated in every manner of crime and corruption, including bank robbery.

When I worked at Orion Pictures after graduation, as first as a producer’s assistant, and then as a low-level development exec, I would see Colors producer Robert H. Solo, who everyone just called “Bob,” on an almost daily basis, as my office was directly down the hall from his production company. We were always friendly, but one day, I did make the social mistake of bringing up the 466 Screening. He had no idea that student was John Singleton, and he didn’t seem to find it interesting or amusing that the kid who was yelling at him had grown up in just a few years to be one of the biggest directors in town. I never discussed it with him again. Bob was proud of Colors and had a big poster of the film on display inside his office, along with a prop crowbar with “May I Come in?” written on the side, which is used by cops in the film to bust open the door of a house where gang members were hiding, specifically in the scene where the girl is arrested naked. I wonder if Bob and Singleton ever met again years later and how that went. Bob was a no-nonsense producer, who was well-respected by the studios for keeping projects moving ahead and bringing them in on budget. I suspect he and Singleton might have worked together well, had they initially met under different circumstances.

In a lesson that perspective is everything in Hollywood, Phil Joanou would direct his third feature, State of Grace, at Orion. While the Irish mob film, which starred Sean Penn, Ed Harris, Robin Wright, and Gary Oldman, has since grown in reputation and has a devoted fan base, State of Grace was only modestly received by both audiences and critics at the time of its release in 1990. I was in charge of putting together “Directors Lists” for various screenplays that Orion owned, to try to “package” them with a director, and I would include Joanou on them as often as I could. However, particularly after his 1992 feature Final Analysis, which starred Richard Gere and Kim Basinger, also was not as big hit as hoped (although its box office was better than its reviews), Joanou had “cooled,” and I was soon told by my higher-ups that he didn’t need to be on our current lists.

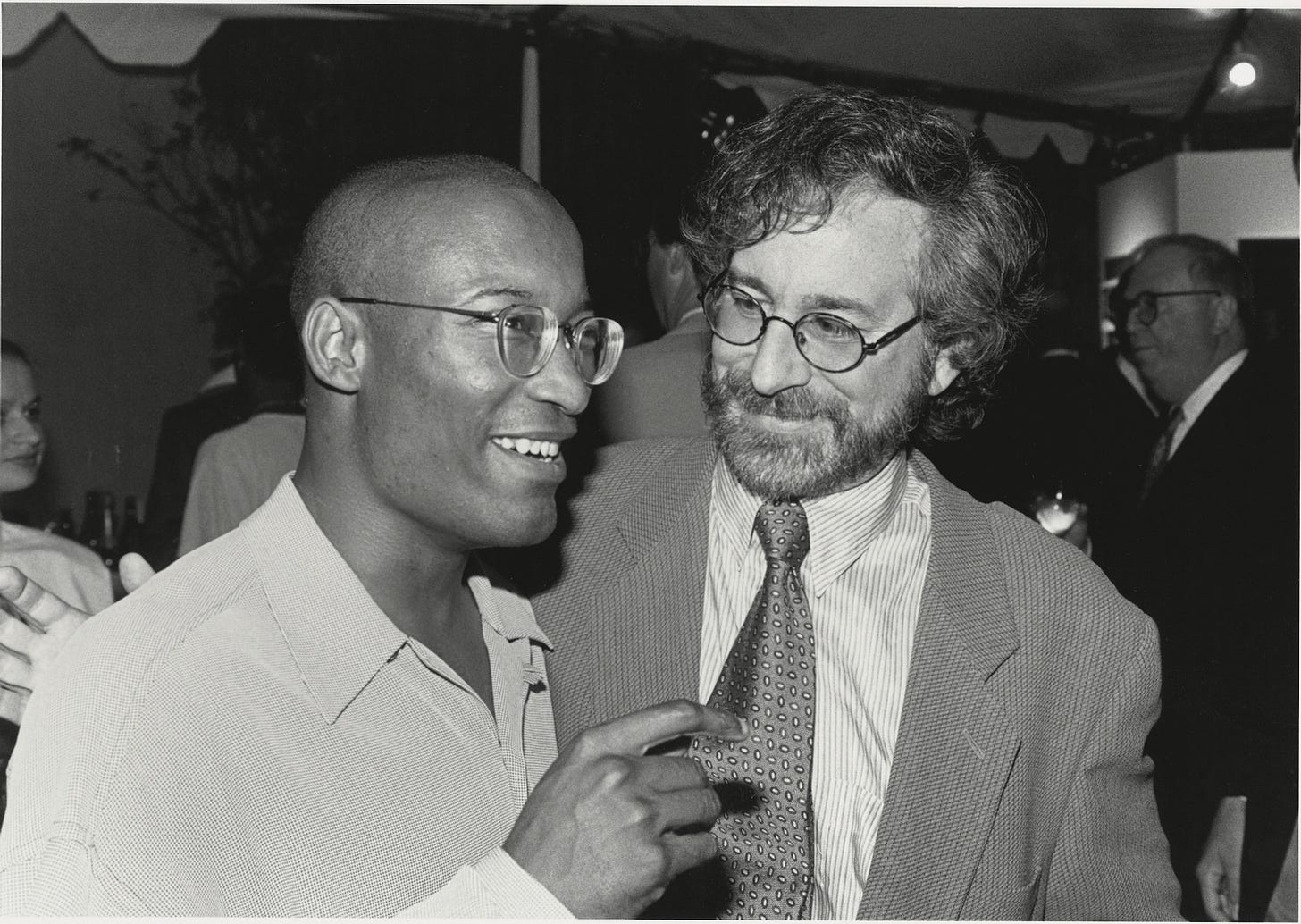

From the perspective of 2025, Phil Joanou did not become the next Spielberg for a new generation of filmmakers, very accomplished though his career has been. I was, and remain, a fan, but the wide influence of his work, nearly four decades out now from his breakthroughs, simply isn’t on the level of a seminal filmmaker. Singleton, however, was arguably the first of the Gen X filmmakers to become an icon, and certainly the first from what could be called my sequence at USC Film School. In his 1994 interview with Conan O’Brien, Singleton referenced the Spielberg and Lucas obsession at our era of USC, remembering, “Everybody there was trying to be like, George Lucas or Steven Spielberg, everybody. They would grow beards that look like Spielberg. And look like Lucas. And they wear the right kind of glasses and stuff. And I was like, you know, people will say, ‘Oh, you’re trying to be like Spike Lee…’ I was trying to be like John Singleton. I was trying to define my own identity, you know, as a person. And then maybe I’d find it if I got a chance to make a movie.” It is worth noting that Singleton also credited Spielberg as a major inspiration for wanting to be a director, after he saw a behind-the-scenes piece on the news show “20/20” about the making of Close Encounters, as a child. The two directors would eventually become friends.

While the twin towers of Spielberg and Lucas cast, both decades ago and today, a large shadow at USC Film School — each filmmaker donated a huge new building in 2009, basically knocking their “old” 1984 models down to make way — John Singleton would also become a reason innumerable new filmmakers picked up the proverbial camera in the first place. Not just at USC, but across the globe.

On the topic of John Singleton’s legacy, Todd “Stereo” Williams wrote for Andscape in 2019, the year when Singleton left this earth way too early, “The success of Singleton’s creative voice was a game changer; it was a generational and cultural push into both Hollywood’s mainstream and black cinema’s more rarefied corners. He made movies for a generation that understood the ideals of the civil rights generation but didn’t always feel beholden to them. His movies could be as brash, and as hopeful, as a great rap album. He demanded accountability in the industry and commanded your attention in his storytelling. With news of Singleton’s passing, we’re losing a huge part of contemporary Hollywood’s soul and black Hollywood’s legacy. But his success forged a path that the Ryan Cooglers and Ava DuVernays now walk — Cali kids who broke through telling stories their way. For almost three decades, Singleton gave us a map to follow.”

None of the principal figures of the 466 screening are with us any longer:

Dennis Hopper passed away from prostate cancer on May 29, 2010, at the age of 74.

Robert H. Solo passed away on August 27, 2018, at the age of 85.

John Singleton passed away on April 28, 2019, of a stroke, at the age of 51.

The weekly 466 screening series continues to this day at the USC School of Cinematic Arts.

SOURCES:

Thanks to the numerous fellow USC School of Cinema-Television alumni who answered my emails about what they themselves recalled from that 466 Colors screening. Unfortunately, no video tape existed of the event, which was confirmed for me by the school itself.

How Boyz n the Hood Beat the Odds to Get Made-and Why It Matters Today

A quarter century later, the cast and crew talk about making the revolutionary film.www.vanityfair.com

John Singleton was Hollywood's first hip-hop director

His first film is an era-defining classic, a movie that helped shape so much black cinema of the 1990s. He cast rappers…andscape.com

From the Window, Rang Two Shots

The Reality Crew "Drive-By Shooting" (Coast to Coast Visions, 1988) I found this song about a year ago during book…ericdharvey.com

John Singleton Brought South Central to the World

The 'Boyz N the Hood' director passed away this week at 51. And he shaped culture in ways we're still trying to…www.gq.com

This Documentary Shows Why Boyz N The Hood Is Still A Classic 25 Years Later (Video)

This Documentary Shows Why Boyz N The Hood Is Still A Classic 25 Years Later (Video)ambrosiaforheads.com

Dennis Hopper's 'Colors' Is The Ultimate Cop Curiosity

With his 1988 police thriller 'Colors,' Dennis Hopper captured the look and feel - if not the meaning - of Los Angeles…theplaylist.net

Everything you wanted to know about 'Colors' but were afraid to ask - POCHO

If you grew up in the 80's and 90's, you remember the film Colors. It spawned a lot of headlines about violence at…www.pocho.com

Looking back at Dennis Hopper's Colors

In 1988, Dennis Hopper directed the controversial cop drama Colors, now reissued on Blu-ray. Ryan takes a look back at…www.denofgeek.com

USC Cinematic Arts | School of Cinematic Arts News

By SCA Staff In the School's hallways and on social media, SCA students, faculty and staff shared remembrances of John…cinema.usc.edu

USC Cinematic Arts | School of Cinematic Arts News

September 2, 2022 By Amaya Nakpodia In 1989, a student of what was then called the Filmic Writing Program (now the John…cinema.usc.edu

USC Cinematic Arts | School of Cinematic Arts News

February 26, 2020 By Desa Philadelphia In Spring 2017, the School of Cinematic Arts' newly re-launched Council on…cinema.usc.edu

USC Cinematic Arts | School of Cinematic Arts News

February 26, 2020 By Desa Philadelphia In Spring 2017, the School of Cinematic Arts' newly re-launched Council on…cinema.usc.edu

No comments:

Post a Comment