In 1994, I confronted my fears of cold-calling by attempting to book one of the great wild men in the history of Hollywood, actor Lawrence Tierney, to appear in our low-budget feature film.

We had to get a celebrity cameo in our movie. Everything depended on it, our cinematic manhood, everything that we ever were, or ever would be, or ever could be… or so we had convinced ourselves.

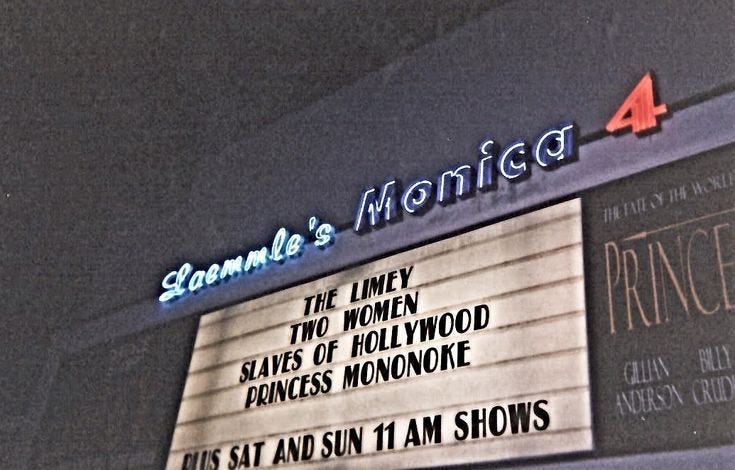

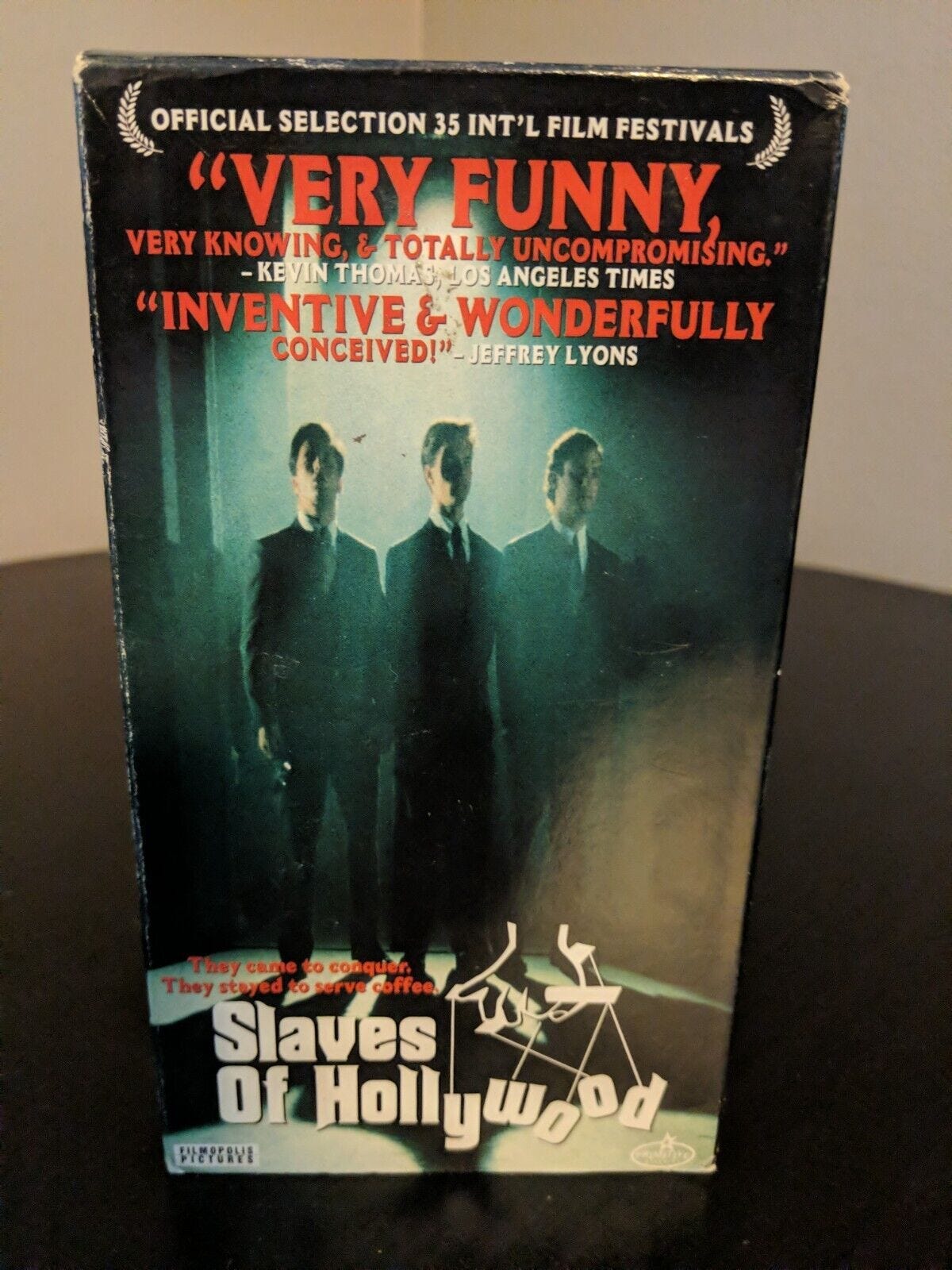

The year was 1994, and Mike Wechsler and I had just shot our first feature film, Slaves of Hollywood, which we wrote together and then co-directed. The satire followed a group of young Hollywood assistants to producers, agents, and studio executives. The tone was based in reality, but with touches of real wackiness. In moments of fancy, and ego, we called the style “hyper-reality.”

Our budget was a little over $100,000, financed by a combination of personal savings, generous relatives, crazy/daring/wonderful friends, and credit cards. Very low-cost for the time, but today, you could do far more with the adjusted- for-inflation equivalent amount due to the cost effectiveness of shooting and posting on digital, as opposed to the 16 mm film which we shot and edited on.

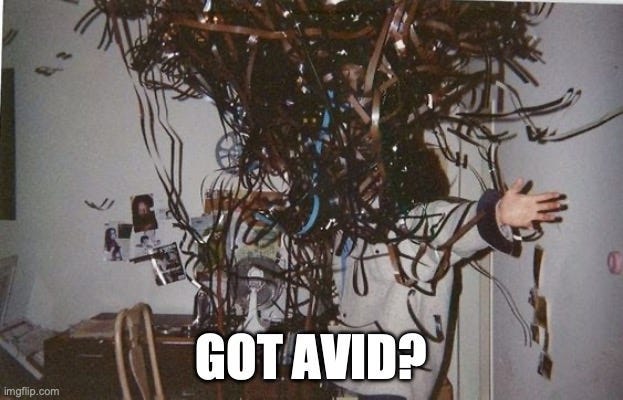

As we moved into the post-production phase of film and audio editing, an enormous “flatbed” Moviola editing deck, which was used to splice picture and audio tracks together manually, took over my tiny apartment living room in West L.A. for two years. That flatbed was the opposite of what your typical young & single 90s guy wanted in his bachelor pad. One friend always jokingly referred to it as the “chick magnet,” but I was essentially dating our film anyway and no magnets were needed.

Making any feature films outside the studio system back then was still fairly unusual, partially because they had to be shot on actual film to be taken seriously. There was still a stigma associated with video, in that you weren’t a “real” feature film if that was your format of choice. 35 mm film was preferable, but 16 mm was still ok for festival screenings, with the caveat that you would have to “blow up” the 16 negative to a 35 negative for theatrical distribution.

Although we had what was regarded as a “real” feature, it was far from a done deal that anyone would ever see a second of it. Unlike today, if you didn’t get a theatrical distribution deal back then, or at the very least a home video deal that got you into Blockbuster and/or Hollywood Video, it was like your movie didn’t exist. There was no YouTube, Tik Tok, Insta, Facebook, et al. Social media was in its infancy, and the closed platform of America Online was what a handful of my friends and myself were using to dip our toes into the internet. But you couldn't screen your feature film on AOL. Still photos alone could take an hour to download from the AOL portal and were just as likely to freeze your screen, knocking you off the dial-up connection and forcing a reboot. Your mom calling at an inopportune time to ask when you were finally going to make it in Hollywood would have the same effect.

One way to break out of the indie muck was to get some type of press mention for your film, in the two main trade papers of Variety or The Hollywood Reporter, or in a major film journal or magazine, such as Film Comment. A few years earlier, both the Hollywood and mainstream press seemed to love stories of do-it-yourself micro-budget filmmakers who had financed feature-length work on credit cards and friends/family/whoever donations. In 1987, Robert Townsend regaled journalists with tales of how he finished his landmark feature Hollywood Shuffle using his credit cards. Robert Rodriguez upped the backstory a notch when he explained that he had obtained some of the reported $7000 budget of his 1992 debut, El Mariachi, by donating his body for pharmaceutical product testing at an Austin, Texas-based company, where you could go stay for a week or two, and take home cash after having “doctors” test pills or skin creams on you.

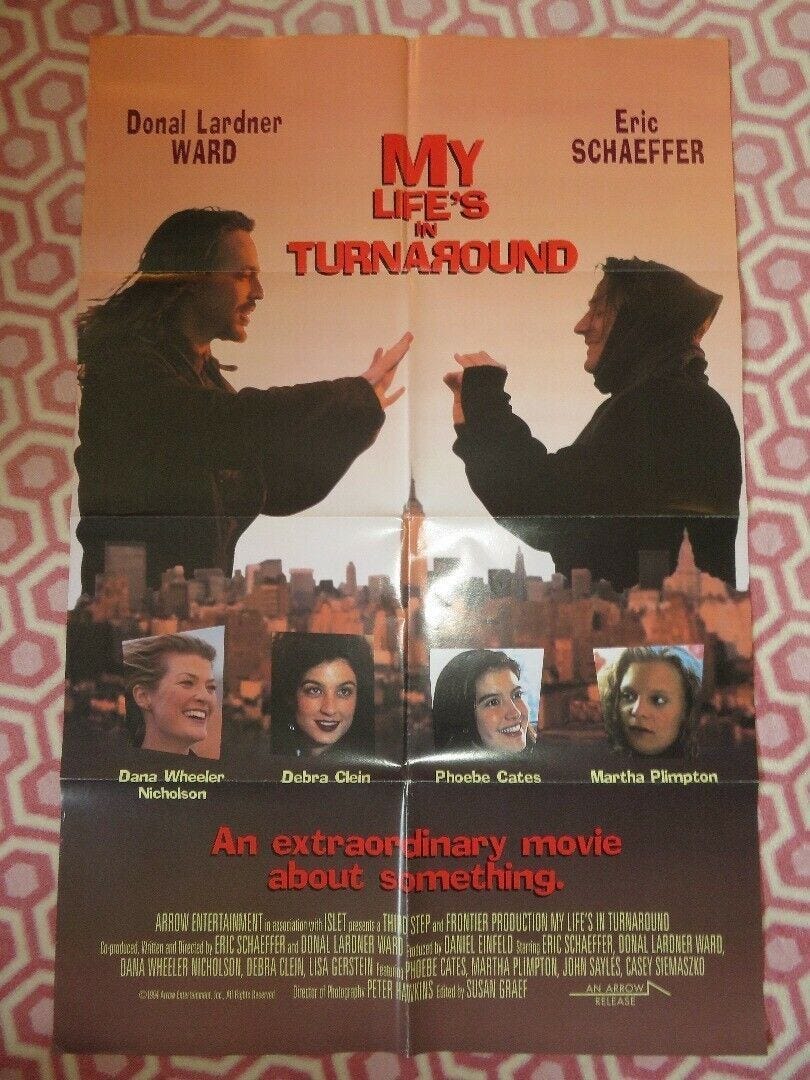

That body experimentation fundraising tale was hard to top, but some filmmakers then put a new spin on the “scrappy indie filmmaker makes good” story by getting actual stars to appear in their little 16 mm epics, for a few minutes at least. In 1993, filmmaker-actors Donal Lardner Ward and Eric Schaeffer had shown what mileage they could get out of cameo scenes featuring themselves and Phoebe Cates, Martha Plimpton, Casey Siemaszko, and indie filmmaking icon John Sayles, in their very funny and charming low-budget feature My Life’s In Turnaround. The plot was even partially about the two lead characters trying to get names to appear in a film they wanted to make. None of those names were huge stars, but they were recognizable talents and that helped garner press attention.

Similarly, Repo Man producer Peter McCarthy directed a film called Floundering in 1994, that featured short cameo scenes with Ethan Hawke, Steve Buscemi, and John Cusack. Those scenes garnered that film a mention in Premiere Magazine, a huge coup for an indie at the time. Premiere was a monthly Hollywood Bible, read by everyone in town, but it primarily covered the studio films and major stars. For an indie to even get a few lines in Premiere put you on the map. Words were not as cheap and disposable as they currently are. Your film could be written about on 1000 blogs today and not get the amount of actual useful publicity, as in quantifiable career benefits, from that one tiny paragraph in Premiere in 1994. By the time Floundering screened at Sundance in January of 94, it had a buzz you could practically hear all the way in my dingy L.A. apartment with my sexy roommate, the Moviola flatbed. This was a brief moment in time when it felt like celebrity cameos could make the difference between your little film ever being watched by someone other than your friends and relatives, and the larger world.

Misguided or not, we saw the “Cameo” as the ticket we needed to get our film noticed above the rest.

One potential hurdle to the Cameo for us was that we had already filmed most of Slaves of Hollywood, but we still had a few scenes to shoot, or more specifically, reshoot. One scene that we needed to redo featured a freakish music video producer character, named Roger Peabody, interviewing his potential new, wide-eyed assistant Fisher Lovelace, played by a twentysomething Hill Harper. The scene, which took place at a wild party Roger was throwing, was chocked with enough verbal and visual sexual innuendo to offend Benny Hill. If John Waters directed the Andy Warhol party scene in Oliver Stone’s The Doors, that might be the tone, or so we hoped.

We needed to reshoot the scene partially because the actor who we originally cast as Roger Peabody just wasn’t… quite right. That was our fault entirely in the casting, as the actor gave it his all. He was funny but a little too buffoonish, rather than funny with a dangerous edge, which was what was needed. I can’t even blame his performance entirely, though, not even close, as there were several other reasons why the scene didn’t work as shot. For one, our Co-Producer, Alan, had kindly offered up his apartment for free to film in, but it had white walls and bland rectangular windows facing out to a street of even more generic, bland L.A. apartments. Roger Peabody needed a sinister, techo-lair of sorts, a real set, and what we had looked like a 1970s West L.A. duplex, no matter what we tried to do to dress it up.

On top of that, even the casting of the minor players in the scene seemed cursed. A character, who was named simply “Sexy Dominatrix” in the script, figured as a part of Roger’s inner entourage. Swathed in a leather catsuit, she was to occasionally crack a whip in Fisher’s general direction, as Roger interviewed him, to create increasing tension. If you’ve seen the Alfred Molina scene in Boogie Nights, with Cosmo the fire-cracker thrower, that is along the lines of what we were trying for. Sexy Dominatrix created tension on the set that day alright, but not in the manner we had hoped. In what seemed like convenient casting, some of our casting agents had met a real-life dominatrix, who also was a professional extra, on another film shoot, and we hired her on their word, without ever speaking to her. It seemed like perfect stunt casting, but the reality… this was not good. Sexy Dominatrix was beautiful, but also was, to put it delicately, acting oddly. Her eyes constantly darted in different directions, and she spoke in a monotone to any questions. This was all before 9 am. I’m not sure exactly what she thought she was being hired for, but her behavior screamed that she may have believed it was a real S&M party, and we were all just play-acting that we were making a movie as the “scene.” The concepts of “action” and “cut” seemed to escape her. She was constantly throwing her whip around, in a pretty dangerous fashion, and freaking everyone out, including Mike, who got whipped in the side of his head while playing an extra for us that day (half of the party extras didn’t show, probably because the pay was so low), and could have lost an eye.

Blocking-wise, Sexy Dominatrix sat on the couch next to Roger in the scene, so she was in most of the wider shots, and we couldn’t “cut around” her performance easily in the editing, with “coverage,” as in reaction shots and close-ups, of the other actors. She would often look directly at the lens, or just stare blankly off-camera, ruining all the wide shots. Did I mention that she also had a few lines to speak?

Trooper that he always was, Hill Harper gamely fought his way through all of these obstacles and still gave a good performance as the freaked-out assistant Fisher, but about halfway-through screening the miserable dailies at Foto-Kem Lab in Burbank the next night, we just asked the projectionist for a mercy killing and he turned the projector off. On the somber ride home, we discussed dates for a reshoot.

A silver lining lay here though. Since we had to shoot the scene again anyway, we decided to recast Roger with somebody famous and finally get our Cameo. During the bulk of the shoot, Michael and I would alternate “directing days.” For efficiency reasons, we never co-directed the same scene, and one of us was always the sole director, calling the shots, with the other effectively acting as a sounding board for creative ideas. We agreed Mike could take a crack at directing the “Roger Scene” this time. I had certainly had enough of it.

Another factor that drove our desire to go big in casting the Cameo was that we had landed an amazing location for the reshoot. A few wealthy young friends of our production company partner Matt, who was also a young law firm associate now, had pooled their considerable resources and opened a restaurant and nightclub on the then-very happening Third Street Promenade in Santa Monica, called Savoy. This place had everything you would want for Roger Scene 2.0, a huge dance floor with disco lights and a DJ booth, along with a plush, and a little sleazy-looking, lounge area upstairs, decked out with beaded curtains and brightly-colored felt couches. The kicker, and most important part: they were letting us shoot there for free. A location that was both great and gratis was a huge deal for our formerly low-budget, now basically no budget left, film.

There was also a deadline now. The Savoy Night Club was available for one Sunday, in 30 days.

We had a month to find a star to do the Cameo.

Our first, and most obvious, problem: we didn’t know anyone famous, not on a personal level, at least. We started pulling at every celebrity straw in our lives that might yield gold. If you lived in L.A., you were only a few steps removed from every major celebrity, but those were big steps. Case in point: at Orion Pictures, I had worked for two years directly across the hall from the Meadowbrook Productions office of Alec Baldwin, then a very popular leading man. While Alec Baldwin wouldn’t have been right for Roger Peabody, as written, we would have sure as hell rewritten the role to make it right. He even vaguely seemed to remember my name and shook my hand from time to time. However, Alec’s assistant, who I was otherwise friendly with, would have laughed in my face if I had asked this favor. The alternative was waiting in the Orion parking lot to ambush Alec with the ask, which may have gotten me tasered by security. No, in general, a current big star was not worth pursuing unless we knew them well.

We strategized. Maybe what we needed was a name from the past, someone who hadn’t worked that much in recent years, but who was undeniably still a star.

Which is how we ended up discussing the casting of the one-time Bernard Schwartz. You may know him better as Tony Curtis.

A friend of a friend, who knew someone at a major talent agency, that being ICM, said that Tony Curtis, then about 69 years old and a long way from his heyday headlining studio films, maybe needed money, and wanted to put the word out that he was willing to do independent features. There were a lot of “maybes” in this whole scenario. Tony Curtis could have been flush with cash and just needed something to do with his days. In fact, when he died at age 85, in 2010, his estate was reportedly valued at 60 million, so perhaps Tony was just momentarily cash-poor in 1994, or, more likely, our intel was all wrong. To boot, Tony and his agent were probably talking about 7–8 million dollar indies when they “put the word out,” not stuff like our little no-budget. None of this stopped us from dreaming of adding “And featuring Tony Curtis as Roger Peabody” to the credits.

I quickly made the sort of mistake of casually mentioning the Curtis Cameo Hypothetical to my Grandmother on Long Island, who had given me some of the money to make Slaves in the first place. I never knew she was a Tony Curtis fan, and suspect she had only ever really seen Some Like It Hot. I do remember she definitely declined to take 9-year old me to The Bad News Bears 3, the one where they go to Japan and Tony Curtis is their manager, so she couldn’t be that big a fan. Nonetheless, my grandmother suddenly offered to put together the money to get Tony Curtis in the movie. She even started writing potential dialogue for Tony and sent it to me in handwritten form. Her suggestion was that Tony could be the narrator of the film, and start out with him in “his mansion in Malibu” (did he even live in Malibu?), reminiscing about his youth in the business and leading us into this story about Hollywood assistants. Creative discussions about literally anything with my Grandmother would often detour immediately into an argument, going back to the high school talent show skits that I would write, direct, and star in, and which she always had creative notes on. So, I just told her “that sounded good, let’s think about it.” Hollywood had provided me with valuable lessons in handling creative disputes, including giving the high-hat to my own grandmother.

While I worked on the financing, Mike volunteered to call Tony Curtis’ agent at ICM, who, somewhat surprisingly, picked the phone right up. (Note: The agent may have been the late Jack Gilardi, famous in his own right for representing movie stars, but our memories on this are not positive.) I was standing by when Mike made the call, and it was a quick one, as he pitched the film and the project succinctly. Mike was good at cold-calling, and seemed to enjoy the wild-card thrills of it. Conversely, cold-calling made me miserable with anxiety, and I was thrilled Mike liked taking on this task for us.

The ICM Agent replied, “$50,000. We’ll give you one day for $50,000.”

Mike: “Okay…”

ICM Agent: “But we have to do it soon. Get back to me.”

The ICM Agent hung up. But Jesus, we could have Tony Frigging Curtis as our cameo. Sidney Falco, the Cookie Full of Arsenic, the Boy with the Ice Cream Face, as Burt Lancaster dubbed him in Sweet Smell of Success. He was practically booked, Dan-O. Tony could definitely play a sleazy music video producer. He excelled at playing cads and near-creeps. But would he? I mean, the ICM Agent didn’t even ask to see the material, but maybe the material didn’t matter so much to them? We would always rewrite it if needed anyway.

I casually told my grandmother about the price. She didn’t flinch, but also didn’t have $50,000, or she did, but wasn’t going to commit to the whole thing. My grandmother could be as cagey as any agent at ICM.

“I think we talk to Uncle Barry about this,” said my Grandmother, in reference to my grandfather’s brother, who was the wealthiest man in the family by a long shot, after a lengthy career near the head of a major tobacco company. “He probably liked Tony Curtis,” she added. “He smoked a lot in his movies.”

Pangs of conscience hit. There was no way I could ask anyone in my family to cough up 50 grand for Tony Curtis, even if one of them, the retired cigarette mogul, likely could spare it. I told my grandmother that we’d have to check on Tony’s availability and get back to her. I instinctively knew that I couldn’t take any more money from family for this project. They had given so much already on blind faith in me. What would happen if we lost all of it? The whole family might starve.

Pooling every dollar we had, Mike and I came to the conclusion that the most we could afford to pay an actor for the Cameo was $500. That definitely would narrow the herd, maybe to none. We were back where we started and the clock was ticking. What sort of name actor could we get for $500?!

“Paul says he has a connection to Lawrence Tierney. Apparently, he’s willing to work pretty cheap right now,” relayed Mike, after a phone call with our producer Paul.

“Who’s Lawrence Tierney again?” said I, who really should have known this, USC Film School degree and all.

“The old bald guy in Reservoir Dogs.”

Oh, this could work. We had reaped creative dividends in Slaves already by “casting against type” in other roles, which could surprise the audience. Lawrence Tierney isn’t what you would immediately think of as the top music video producer in Hollywood, but that’s exactly why it could be memorable. Casting against type could also obviously be a complete disaster. You didn’t cast Wallace Shawn as Maverick in Top Gun, although I would love to see that.

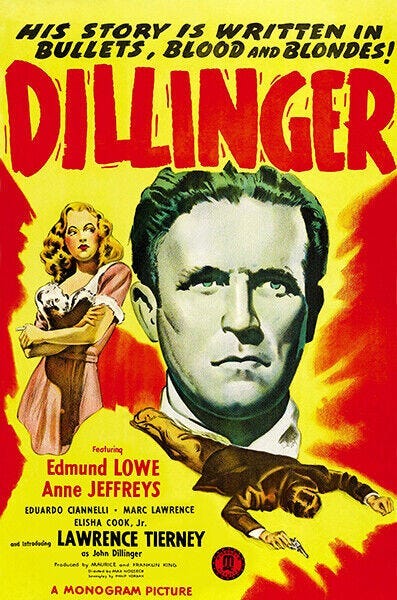

The truth is that, although we considered ourselves cinephiles, we really knew little about Lawrence Tierney. We had heard of Dillinger, but neither of us had seen that 1945 film which had made Tierney a star, nor were we really aware of any of the later Tierney noir classics, at most by title only.

Anyway, what was important to us was how Tierney looked and acted now, not 38 years prior, so Mike and I went out to the Brentwood Blockbuster immediately and rented their one copy of Reservoir Dogs. I hadn’t actually watched Dogs when it was released in the Fall of 1992, but I had seen publicity stills in the trade papers and knew what Lawrence Tierney generally looked like. Although it seems in retrospect that Tarantino just exploded into full being the moment Dogs first screened, the build of his soon-to-be comet of a career was a little slower than that. My screenwriter roommate Alex had raved about Dogs, which he saw at a special press screening, and the film had taken Sundance by storm in January of ‘92. But Tarantino was never even mentioned when we were putting together potential Director Lists for our studio projects at the Orion Pictures production company I worked at in 1992. There was just less crossover between the indie world and the studio film world in the early 90s. Pulp Fiction, with Miramax and Jersey Films behind it, had garnered ink in the trades with each casting announcement, but also a few snickers with the news that John Travolta, his headlining career then deader-than-disco, was a lead. When Mike and I popped in that VHS of Dogs, the rapturous reception of Pulp at Cannes in May of 94 still loomed a few months out in the future. As the “Dogs” argued about tipping in the diner prior to the big heist, my first real introduction to Lawrence Tierney began.

As the big boss Joe Cabot, Tierney simmered, an old gangster filled with barely-suppressed rage that felt ready to explode outwards at any moment. A senior citizen-version of the Hulk, and whose craggy features also looked like the Hulk’s main Marvel Comics rival, the Thing, a fact directly referenced by Tim Roth’s character in the film. Tierney felt more than the physical and mental equal of the far younger group of actors, who played the jewel thieves that crime boss Cabot puts together for a job that goes wayyyy awry. Even real-life ex-con and bank robber Eddie Bunker, who played Mr. Blue, felt like a relative kid, and a sweetheart, compared to Tierney. When trying to compare Tierney to any modern actors, maybe Dogs co-star Michael Madsen came close. Not necessarily someone you wanted to see do Shakespeare, but who had a malevolent screen presence that felt totally authentic.

Mike was always the go-to one of us who could knock out some quick scene pages, to see if they would work. The same endeavor might take me a week. Mike ran off to Java Joe, our favorite coffee house around the corner on Santa Monica Blvd., and wrote a quick draft of the potential scene with Tierney. He brought it back a few hours later, and I read it on the early model Apple Powerbook, which we shared ownership of. I loved the bare-bones of the freshly-scripted scene.

“I imagine Tierney in a bright red smoking jacket, and smoking a cigar. We’ll backlight him and his head. I want him to look like the devil,” explained Mike.

Okay, we had to do this. Hill Harper as the young assistant, and the terrorizing Tierney, as his boss, were going to be a great pair. Tierney was perfect for us!

Just as important, he might even need us. Lawrence Tierney had been a rising star in the 40s and 50s, before a major career downturn. While Reservoir Dogs should have made him in high demand again, it somehow hadn’t, the reasons of which we should have looked a little more closely into. He had definitely done a few projects after Dogs that were on the very low-budget side, such as the recent 35-minute short film Red, which will figure a bit later in this tale.

Our measly $500 might actually land him then, having heard that “Larry always could use money” from our tenuous connection to Tierney: Joey, a performance artist and writer who published a physical zine every month, or maybe every few months, which covered cutting-edge art of different stripes in Los Angeles. Joey was a close friend of producer Paul, whose Brentwood apartment had become the go-to place for meetings related to the film. Joey was frequently there as well, just hanging out, and on this night, having pizza with us. How Joey was friends with Tierney was also tenuous, but Joey knew lots of show business characters, seemingly through his zine.

Still, Joey was adamant that, “You can use my name to speak with him, but it’s your deal after that. If it goes south, don’t drag me into it.”

“No problem,” I told Joey. “What’s going to go south?”

Joey shrugged, “Just sayin’.”

“So you’ll tell him that I’m calling?”

“I already did. He said to give him a ring. Not too early, he’s not a morning dude.”

Wow. Joey had already laid the groundwork. This was exciting. Joey reached into his upper pocket, checked a pocket notebook, scribbled on one sheet, ripped the page out, and handed me Tierney’s 213 area code phone number.

“Remember, keep me out of this now,” asserted Joey, before going back to his pizza.

The general standoffish manner in which the usually gregarious Joey offered me the set-up for our big cameo should have been a warning.

Mike called his Uncle Morty that night and told him we were likely to land Lawrence Tierney for our reshoots. Morty was an entertainment lawyer now, but he had once been Co-President of one of the major studios in the late 60s and early 70s. He was our unofficial advisor on the film and wanted to be kept abreast of any and all developments.

Morty also relished in playing the Devil’s Advocate to the pair of bright-eyed dreamer neophytes that his nephew and I definitely were. No matter what news we’d bring him about the film, including things like this that we were excited about, he would always manage to spin it around into something that created doubt as to whether we had any idea what we were doing in show business.

“I thought he was dead,” said Morty, not as a reference to Snake Plissken, because Morty didn’t do pop culture references, but in all seriousness.

While Reservoir Dogs had been released, the stories about Lawrence Tierney from the set of that film had not trickled down to me, or really anywhere else of note. We asked Morty what he knew about Tierney.

“Only that I heard he was nuts,” replied Morty, and added, “I remember something about the LAPD driving him to the Arizona state line in the 50s and telling him not to come back.”

This is one of the many Lawrence Tierney legends that abounded, and I eventually heard this tale a lot, although Morty was the first to bring it up. To this day, I don’t know if the Arizona state line story was true. It seems like a hell of a drive for the cops to deal with one actor.

Morty also added, “You think that maybe his cameo might HURT your film?”

So many questions to consider. But the answer to that one was no, but also maybe? I don’t know. What were these wild stories Morty was referring to? And what difference, now that Lawrence Tierney was in his 70s?

Regardless, the next morning, I volunteered to be the one who called Tierney, even though this would have normally been a better job for Mike. I wanted to prove I could do it, and I knew that cold-calling was something I had to get better at. Negotiating too. About a year prior, I had mentioned the latter to another friend of the same age, and he gifted me with something that he said had helped him with the same problem: a set of cassette tapes on negotiating by Herb Cohen, the self-proclaimed “World’s Greatest Negotiator,” who wrote the book You Can Negotiate Anything, and who had this go-to catchphrase when things went rough in a negotiation: “Whoa, wait just a minute!” I’m not sure I learned anything from those tapes, but we were about to find out.

In addition to the books-on-tape method, there was a jumping-into-the-deep-end-of-the-pool strategy to the way my twentysomething self conquered various fears. Nervous about talking to girls at parties? I’d make myself talk to five that night. Now maybe I would get great at cold-calling and negotiation from this one conversation with Lawrence Tierney. At the least, I would get better. I honestly couldn’t get much worse.

I’d have to finish actually dialing the numbers first though, which was always the biggest hurdle for me when making a stressful phone call. I’d stop and start quite a bit. This was not a new problem. In high school and college, I had a tendency to even hang up on the call recipient once when making a stressful phone call, before then making a second call and actually following through. These were in the days before Caller ID. Hanging up on someone seemed to be a pervasive societal dysfunctional impulse of the day, as I had the reverse happen to me all the time. The phone would ring, I’d answer, and then the caller would quickly click off. A few minutes later, it would ring again but the caller would stay on this time. It might be somebody you had called about business, or were thinking about dating, or just about anything. You knew they had been the one who hung up, but weren’t sure why, and no one usually pointed it out.

Regardless, I was determined not to hang up on Tierney even once. Larry’s area code was 213, which covered much of Hollywood and Downtown L.A., and I dialed parts of that 213 numerous times, then hung up and started again, before pushing the last button and finally letting it actually ring.

A gruff male voice answered.

“Hello?”

A television set was blaring in the background with what sounded like a war movie, one that I didn’t recognize and so it was likely older. Explosions and gunfire and soldiers shouting.

It was definitely him. Nobody else alive sounded like this. I wasn’t sure how to start. I didn’t feel like just saying “Hi, Larry?” was going to be appropriate. Little did I know how little my own version of being “appropriate” was going to matter in this relationship.

“Hi, I’m trying to reach Lawrence Tierney.”

“Speaking!!!”

As I would quickly learn, Larry would frequently yell in conversation, and I’m not sure whether it was because his hearing was bad, or the television was just so loud. I’m positive he wasn’t always as contentious as he sounded. He just couldn’t hear, for reasons physical, mechanical, or both, so every conversation eventually became like having a screaming match with Joe Cabot. With the television always going, both you and he were struggling to hear, and be heard, over what felt like a constant stream of old war movies, which always seemed to be on during battle scenes. Now there was cannon fire.

“Hi, my name’s Terry Keefe. Our mutual friend Joe Poplowski talked to you about the feature film we wanted to, um, offer you a role in?”

“I don’t know any Popalowski. Polish? Don’t know him.”

“Poplowski.” I corrected.

“Uh-huh,” grunted Larry.

Long silence. Joey had to know Larry. This was his phone number he had given me. Also, the last thing I attributed to wacky Joey’s identity was that he was Polish, but this seemed to matter to Larry.

I was ready to throw in the towel here when Larry rescued the call.

“Keefe…Irish?”

“I am!” I exclaimed, grasping for any common ground here.

“Yeah, so am I.”

I never knew what to say when anyone who was proudly Irish-American, but who inevitably called themselves just plain Irish, tried to bond with me over it. Despite being Irish myself, I was brought up by Russian-Poles who barely knew when St. Pat’s Day was. Larry was of a New York generation where your ethnic and/or religious self-identity was very important, though, and I was happily Irish now.

“Cool, that’s awesome!” I replied, with as much enthusiasm as I could muster. It sounded convincing on my end. I wasn’t going to sing “Molly Malone” to win him over. Well, I probably would have at this point.

Explosions from the war movie. Long silence from Larry. Well, not totally, because he was breathing heavy. He cleared his throat loudly a few times.

“What kind of picture are you making?!” Larry finally blurted out.

“It’s called Slaves of Hollywood.”

“Porno?”

We had heard this so many times, from so many people, that we should have known we had a serious marketing problem with that title. We hadn’t actually borrowed the title from Slaves of New York author Tama Janowitz, which is something we were also frequently asked. The original name of the film was, in fact, KNAVES of Hollywood. A friend suggested SLAVES of Hollywood and it just rolled off the tongue better, but somehow adding “Hollywood” provided a porno vibe not quite there in Slaves of New York.

It didn’t appear that Larry was necessarily turned off by the prospect of being in a porno. He was still on the line.

“No, no, it’s not a porno, Larry. It’s an indie comedy about working in the film business. We have to reshoot a scene and wanted to cast you. It’s a day of shooting. We’ve written the part just for you.”

“Ah-hah. It’s a pick-up.”

“Right, a pick-up!”

“And we wrote it just for you!”

More silence from Tierney. Bomber planes on the television.

“How much you offering?”

“Ah, $500?”

“That’s….that’s the best you can do, eh?”

“Yeah, I’m sorry, but cash. We’ll pay you in cash.”

“Of course I want it in cash!”

Another long silence, but maybe we were getting somewhere. In this scenario, we were at least exchanging money somewhere, sometime, in exchange for his acting services. Felt like casting to me!

“I’ll do it for $600,” Tierney suddenly grunted.

That extra $100 might mean we didn’t eat that week back in those days. That is how broke we were, but who needs food when you can have the CAMEO?

More silence from Larry, who then burst out, loudly, “$600 then. We have a deal for your picture.”

This may have been the easiest negotiation I ever had. Despite his gruffness, Larry spoke in the sophisticated-sounding parlance of many older Hollywood players, when he referred to movies and films as “pictures.” We were making pictures! So much more elegant than just movies.

He asked for my phone number, which he repeated to himself as he scribbled it down.

“Okay, I’m gonna keep that number by my phone. Give me a call tomorrow and we can figure out a time to get me those script pages. I’m going out to Arizona in a few days to look at some land, so let’s talk before then.”

We seemed to be all set! Maybe it wasn’t that difficult to get a celebrity to do a cameo in your picture. Or maybe it was because I was That. Damn. Good.

I told my grandmother the great news. Crickets on the line in Greenport, Long Island. She vaguely remembered Tierney from her younger moviegoing days and that he was a “tough guy actor.”

She added, “I thought he was dead.”

Fans of the Tim Burton film Ed Wood may remember this as a frequent reaction when Ed would boast about having Bela Lugosi in his upcoming projects. That I was heading into Edward D. Wood territory myself in my general career and filmmaking approach was sort of lost on me at the time. I had gone from being a rising development guy at a major film studio to whatever the hell I was doing now. All in two years. Oh, the places you’ll go.

“Tony Curtis would still be better,” concluded my grandmother, who had attended the famous Girls’ High in Brooklyn, and was only two years younger than Larry, who had attended the related Boys’ High. They were practically neighbors in the same era and could have potentially met at an ice cream social between the schools. Larry was surely one of the most famous people to come out of the neighborhood in that time period, along with Norman Mailer, who also attended Boys’ High, albeit a few years after Larry. One might think my grandmother would have more knowledge of a famous actor she grew up near, but she barely knew who he was these many decades later. Maybe this wasn’t such a great cameo with the general audience then, but my grandmother wouldn’t have made it through five minutes of Reservoir Dogs either.

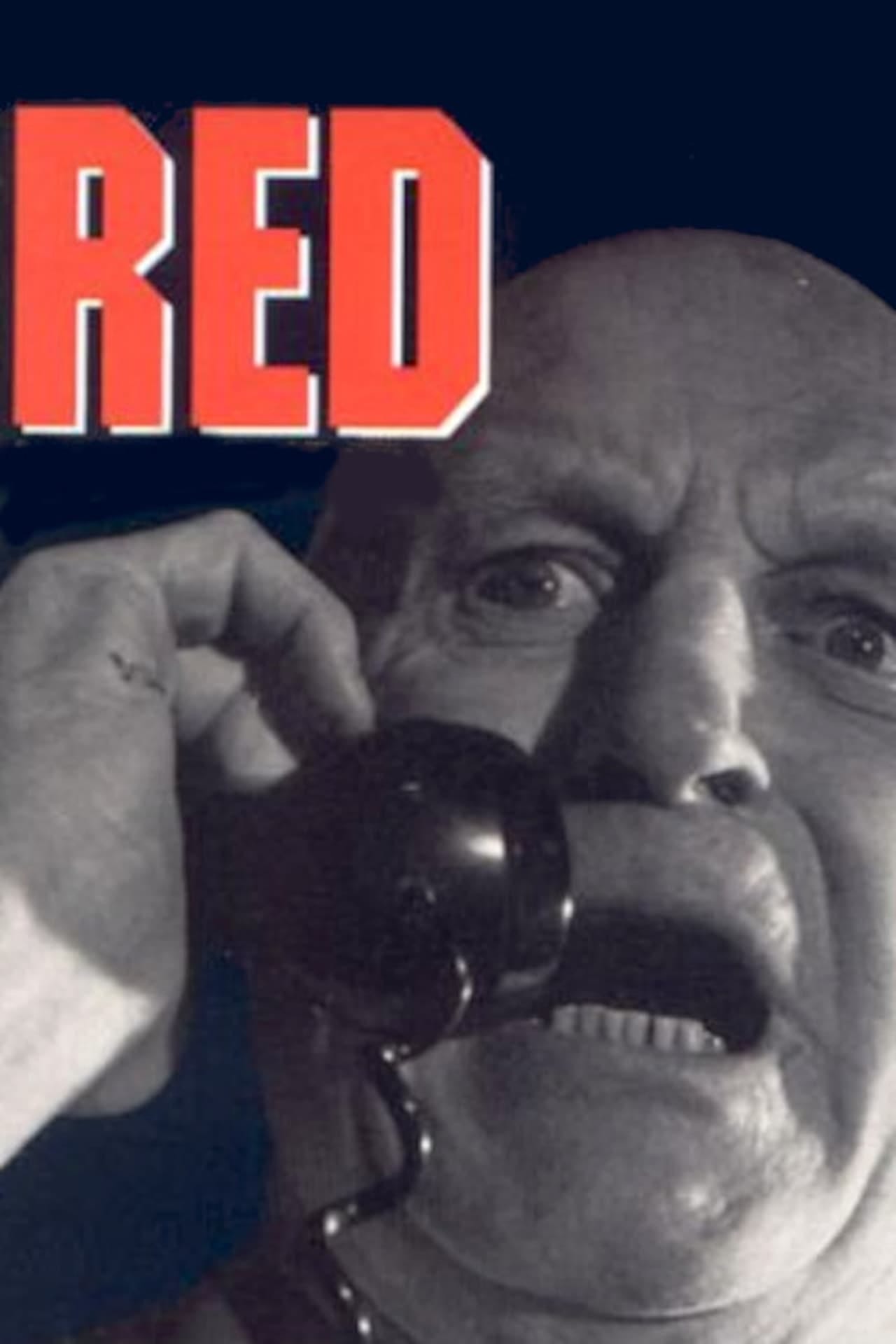

Regardless, that evening, Mike and I celebrated. Well, we got coffee at Java Joe and then watched Larry’s recent film Red, the low-budget short that Chris Gore (billed in the credits as Christian Gore), founder and editor of the seminal magazine Film Threat, had directed, sometime shortly after Reservoir Dogs. Gore’s magazine was a vital, and influential, part of the independent film scene in the 90s. Film Threat had a punk rock edge to it, and whereas other indie film mags would be covering the latest Sundance discovery, Film Threat might write about directors and projects that virtually no one else was even giving a word of ink to.

In the film, Tierney plays the titular “Red,” the real-life Jersey bartender (Louis “Red” Deutsch) who was the victim of phone pranksters at the Tube Bar in Jersey City. The ‘Tube Bar Tapes”, in the pre-internet days, went the analog version of “viral,” via cassette tape trading, and featured a pair of prank callers, later revealed to be named John Elmo and Jim Davidson, who recorded a series of calls to the Tube Bar. Red the Bartender would pick up the phone, be duped initially, but then become increasingly verbally violent as the callers provoking him. The Tube Bar Pranksters were sort of spiritual grandfathers to the Jerky Boys.

(Tierney on the cover of the VHS of Red, above.)

Sample dialogue:

Prank Caller: Is Al there?

Red: Al who?!

Prank Caller: Al Coholic.

Red: (shouts to the bar) Is Alcoholic here?

The bar erupts into laughter and Red realizes that he’s been had.

Red: (back into phone) “Why you ***king son of a bitch! I’ll kill ya!!”

Rinse and repeat. A few hours later, the caller dials the bar again and gets Red.

Prank Caller: “Is Ben there?”

Red: “Ben who?”

Prank Caller: “Ben Dover.”

Red (shouts to bar): “Is Bendover here?”

Laughs from the bar patrons, as Red realizes he has been taken yet again, and turns back to the call with absolute fury, shouting,“You’ll remember me for the rest of your life!! You sunovabitch, I’m gonna -” Red then unleashes a torrent of descriptions of what he will do to the Caller’s mother, rectum, testicles, and the same of all his family members, mixed with every manner of swear word and insult.

The Red of Gore’s Red eventually is driven insane by the incessant calls and starts actually killing his tormentors, who have unwisely shown up at the Tube Bar and identified themselves to him. The beleaguered bartender finally pulls a shotgun from behind the deck and blows them away in a bloody massacre.

We had now seen the modern-day version of Tierney in two films, and what was dawning on us was that he was maybe more of a great presence than a great actor, per se, but a great presence was plenty for us.

The next day, Mike and I relayed the Tierney Casting Good News to attorney friend Matt, who wisely made the point that we had better get our new star under some type of contract. If we didn’t have this deal in writing, we could easily get the rest of the cast and crew together at Savoy …and Tierney might decide not to show. There was no arguing the logic of this, but it felt like a potential road bump. Another hurdle to make this fantasy cameo come true. Because while my negotiating skills were still developing, I did know that getting somebody to sign an actual contract potentially could be a lot harder than getting them to verbally agree to a deal.

Matt put it sympathetically, but bluntly, “T, there isn’t really a deal with this guy unless we have him inked.” Matt would generally call me “T” when he was telling me something he knew I needed to hear, but didn’t really want to.

I told Matt I’d let Tierney know about the contract, and about an hour later, after several false starts but no actual hang-ups, I called Tierney again. He picked up right away, but there was no television blaring this time. If it weren’t for his unmistakable rasp, he would have seemed like a different person. His voice was calmer, and more measured.

I reintroduced myself, explaining we had just spoken last night and had negotiated a shooting deal, and that I was hoping to memorialize our deal in writing. For our picture. That last part I said as quickly as I could, hoping to just get him to a “no problem” right away.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.” Silence on the other end, and I had to ask if he was still there, which he was.

I had no idea what to do here. I tried explaining again who I was, in case he needed reminding.

“Yeah, I don’t think I can help you out with this picture,” he said, flat and emotionless as can be. I couldn’t tell if he just didn’t remember our big negotiation from last night, or if he was now saying “No” to me, after sleeping on it. Was it because I mentioned a contract? The voice of Herb Cohen echoed in my head, but before I could even blurt out, “Whoa! Wait just a minute,” Larry concluded the call himself.

“I’ve gotta go, sorry” and he hung up.

My Cameo dreams were dissolving before my eyes. This time I didn’t need my pre-call ritual of false starts. I re-dialed Tierney straight through immediately. Like a boss. Okay, I would tell him that we would forget about the contract for now, maybe for good. If I had the money, he was going to show up, right? He surely needed it for that Arizona Land Deal. Wasn’t that what they were selling in Glengarry Glen Ross? Always. Be. Closing. We didn’t need a contract. And if people saw him take the money from me, and he did the shoot, hell, there should be no problem making a case in court that he agreed for his image to be used.

But, the phone rang and rang. He had no answering machine, which was unusual for an actor at the time, yet this was no ordinary actor either.

I tried again an hour later. He was definitely avoiding me. Caller ID didn’t exist, so he was willing to not pick up that phone, and potentially lose other more important calls, just not to take my call. That boded poorly.

Mike wasn’t thrilled when I told him what happened, but he also wasn’t that surprised. Maybe he had little confidence in my nascent dealmaking abilities, or maybe he was a bit relieved. He confided, “Look, it might have been the Shoot From Hell. It sounds like he’s a little off, or maybe way off. If things went wrong somehow, like he just ditched us, we’d lose our shirts on this shoot.”

I dozed off that evening around 10 pm.

The phone rang around midnight. This usually meant somebody died back home.

I stumbled to get the phone, knocking it off its base. This was before Caller ID, so there was no way to know who on the other line.

Loud television dialogue greeted me as I mumbled a hello.

“Keefe?”

“Yeah?”

“It’s Larry Tierney! When are we shooting the picture?”

The images of Larry from Red, angrily shouting into the phone, invaded my mind.

“Larry? I thought you didn’t want to do the picture… or something?”

“What are you talking about?! I told you I would keep your number by my phone. We’re supposed to be making a picture together! 700 bucks!”

“600.”

“Okay, fine. Can you do the 7? See if you can do the 7.”

“Okay, I think we could do that, but that’s all,” I replied, trying to be stern but also wanting to keep my deal together. I was now up to 700 bucks, but still worth it for the Cameo.

It was only later that I realized Larry had negotiated another $100 out of me. Was this the method to his madness? Herb Cohen would have hit me with his book.

“I’m heading out to Arizona for a few days to look at some property there. Land. Let’s get this all locked before then,” Larry said. Arizona and that land deal again. This reminded me that I wanted to ask him if he had ever actually been driven to the Arizona state line and dropped off by the L.A. cops, but I resisted. Maybe that story really happened and he had developed a whole separate life in Arizona since then, with a wife, kids, grandkids. He might need the land to build an extra house for his expanding family. I did get the impression that our 600, now 700, bucks was maybe key to this real estate purchase he hinted at.

The sounds of movie dialogue from his television echoed.

“Have you ever seen this picture I’m watching?”

I started to reply that I’d have to know what it was first, but he cut me off.

“Breaker Morant. Such a great picture.”

I agreed, although I hadn’t yet seen the 1980 film. Based on Larry’s recommendation here, I did see it later that year, and he was right, it was a great picture, but it wasn’t MY picture.

“Larry, I’m glad we’re doing this. There was still that thing with getting a contract -”

He cut me off again. “Why don’t you give me a call tomorrow, and we’ll arrange a time for you to come by and give me those script pages, and I’ll sign whatever you need.”

All sounded okay, although I was a little nervous about how he ended the call quickly when the contract came up. We said goodbye, hung up, and I went to sleep like an auteur baby, pretty confident in the future of this shoot and my career.

The next morning, I decided to give Larry until 11 am or so before I called. He likely had been up late watching the rest of Breaker Morant. I didn’t want to wake him. Larry was an older guy, after all.

Larry picked up after a few rings, his tone somber.

“I don’t think I can do the picture.”

I was shocked and fumbled for an unprepared answer to this. I didn’t think a little indignation was out of line, so I added some to my tone.

“Larry, I thought we had a deal!”

“No.”

“I’ll pay you cash.”

“Of course you’ll pay me cash -”

That sounded hopeful again.

“- but no. Can’t do the picture.”

“Larry, is there anything I can do to get you to change your mind?”

“No.” A pause. “I’m sorry. Goodbye.”

Larry hung up. Even Herb Cohen would have been exasperated by now.

I didn’t have the heart to tell Mike a second time that Tierney had dropped out. Just as well because later that day, as in much much later, circumstances changed once more. I had gone out for a bit, and when I returned home after midnight, there was a message on my answering machine which took up the entire side of the cassette tape. An hour in length. What the hell was this?

Larry had called. His television was blaring what an announcer kept name-checking as “Racing from Santa Anita.” Horns to start a horse race followed by the frenzied announcer doing play-by-play of the horses galloping around the track. Larry shouted into the phone over the din of this racket.

“Keefe, it’s Tierney! I still haven’t gotten those script pages!! Drop them off to me here at the Hollywood Tower Apartments…”

A loud rustling sound, then louder clumping and slamming noises, and the phone seemed to hit the ground. I listened for Larry to pick up the phone, but that never happened. My cassette answering machine was sound-activated, and as long as there was any audio whatsoever on the line, it just kept recording, until the tape ran out and abruptly cut off. An hour later.

Did Larry gamble on the horses and suddenly decide he needed our shoot to cover a bad bet? I kept listening…for the next hour, as “Racing From Santa Anita” ended and an episode of “Dr. Who” started, likely the Tom Baker-starring version, from the theme song that I knew from childhood. I liked “Dr. Who” at least. Finally, the tape just cut off. Did Larry die? Should I be calling 911? I probably should have, but I didn’t. Somehow I knew that Larry had just passed out, or fallen asleep.

Plus, he had given me his address, or at least the name of where he lived. I could find the rest. This day had been good to me after all.

The next morning, I decided I wasn’t going to call Day Larry. My plan was to just drop the pages off at the Hollywood Tower Apartments and leave them there for Larry. Day Larry would probably pick them up, but odds were it was Late-Night Larry who would read them and hopefully love them. I would thus avoid direct contact with Day Larry, who seemed to not know who I was.

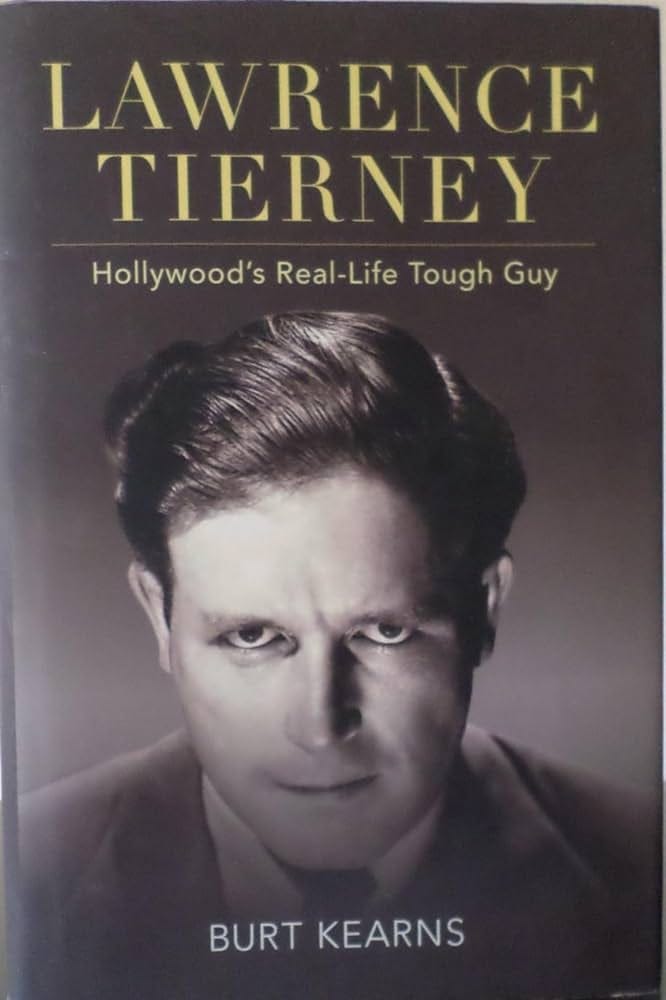

Late-Night Larry was a different story, and I had the impression that Larry would maybe have a few drinks, see my number on the little scrap of paper he kept by the phone, remembered about the project, and gave me a call. Day Larry had no memory of this whatsoever, or maybe just a fading memory, like a conversation you had after five cocktails. Larry was certainly an alcoholic, and had actually been very open about his participation in Alcoholics Anonymous during his mid-century heyday, but, to be clear, I have no way of knowing if he was still drinking during these later years of his life. Friends in the terrific 2022 biography of Larry, Lawrence Tierney: Hollywood’s Real-Life Tough Guy, by Burt Kearns, speculated that Larry may have been manic depressive and that was a possibility here also. Regardless of the cause, I was negotiating with two Larrys, effectively. Hey, my method was dive into the deep end of the pool, right? Even if there might not be any water in it.

I cruised out to the Hollywood Tower Apartments, which was several stories tall, somewhere near Highland Blvd., and which looked like it could collapse during the next earthquake, hell, the next aftershock. Larry could probably even knock it over by punching the wall during a tough negotiating call with me. A lot of people lived in this place, and somewhere, in one of these apartments, Larry and I had been hammering out our deal over the phone. I wondered what his neighbors thought of his television volume, and I felt sympathy for whoever they were.

(Note: The Hollywood Tower Apartments is what I remember the apartment building being called. A current search of Google reveals a very different-looking building of that name, than I remember, far more expensive-appearance and more like a boutique hotel, so it is possible Larry’s building was called something else. The old building he lived in may also just be gone, or the version seen on Google was a renovation.)

A good-looking Young Actor Type sat behind a desk. Not exactly a doorman, but his job seemed to be to watch the lobby.

I approached, “Hi, I needed to leave something for Lawrence Tierney.”

That name needed no introduction. “Oh, yes!” he nodded, quickly taking the papers from me. I thanked him and headed off. Over my shoulder, I saw the Young Actor Type pick up the phone, presumably calling Larry. He then flipped through the script pages himself with interest. I took off before Day Larry made an appearance in the lobby.

On the way home, I spontaneously decided to make a stop at the Beverly Hills Public Library, where Mike and I had done a lot of fruitful research for Slaves of Hollywood, as they had a huge microfilm library of magazines and newspapers, going back many decades. Long before things were digitized.

It was time to learn everything I could about Lawrence Tierney. I was so excited about us working together that I wanted to read up on his early films and learn more about the guy we were going to shoot this scene with. These were the days when the library was the best place for most types of broad research. I was going to regret this stop, though.

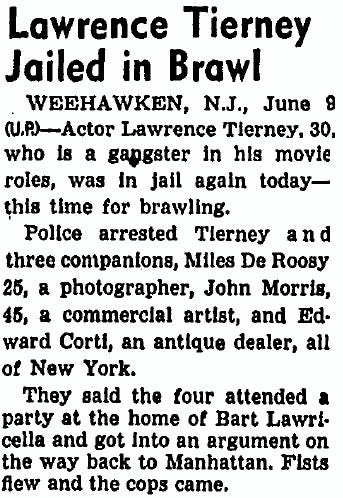

Over the remainder of that afternoon, I pulled newspaper articles and gossip columns going back to the 1940s, and I learned pretty quickly why Larry had had his career end several times, although I was not quite sure why he was able to come back several times as well with new projects. Bluntly, Larry might as well have been the person the phrase “raging alcoholic” was invented for. In his legend-making days of the 40s and 50s, he was arrested at least twenty times for fights in bars, nightclubs, and with cops. Not just in L.A., but in New York as well, and several states in between. This Hulk-like cross-country ramage continued well into the next decades.

If there was a Day Larry and a Night Larry, Drunk Larry could be added as a third persona, and it was the Larry you really didn’t want to meet. Drunk Larry seemingly would just punch other bar patrons, unprovoked. The Los Angeles cops beat him with night sticks on more than one occasion, for resisting arrest, and maybe just because they were so sick of him. Enough to drop him to Arizona? Maybe, but probably not. The legendary gossip queens Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons loved writing about Larry, and often led with his most recent antics in their regular show biz columns. During the 40s and 50s, Larry tried to choke a cab driver, hit a waiter over the head with a sugar bowl for refusing to sell him more drinks, was put in jail for 90 days for breaking a college student’s jaw, and also placed in a mental institution after being found “disheveled in a church.” These were just some of the highlights.

The articles revealed that Larry managed to end, and subsequently jumpstart his career more times than virtually anyone in Hollywood history. He had been on the career skids after losing his RKO contract, when he got a significant role as one of the main villains in The Greatest Show on Earth, which won Best Picture in 1953. His co-stars included Jimmy Stewart and Charlton Heston. Legendary director Cecil B. DeMille apparently loved Larry, promising him a multi-picture deal. Which Larry managed to scuttle when he made the papers again for getting in fights and being arrested for the umpteenth time.

Larry was reportedly the favorite of equally legendary director Elia Kazan, to play the role of Charley, the brother of Marlon Brando, in On the Waterfront. For reasons unknown, Larry demanded too much money and the role went to Rod Steiger, who received an Academy Award Nomination for the film. Steiger’s career skyrocketed afterwards. Years later, producers apparently wanted Larry for the lead in the John Avildsen film Joe in 1970, but the role went to Peter Boyle after Larry reportedly urinated on someone during the wardrobe fitting, and, for good measure, was also arrested for assaulting a bartender that week.

As Larry’s career continued to death-rattle and then somehow resurrect itself again, his younger brother Gerard Tierney, who had sort of followed him out to Hollywood, gradually built a very successful career in movies and television, in a pretty stable and consistent fashion. He worked under the name of Scott Brady, which turned out to be helpful in separating him PR-wise from Larry’s antics. In terms of his acting style, Scott Brady was warmer on screen, sort of a more accessible version of his brother, who he definitely resembled. While his onscreen persona didn’t burn with the pure malice of his brother, whose did? Brady had a lot more luck than Larry did in being cast in hero roles, though. Between 1959 and 1961, Brady would star in his own western television series “Shotgun Slade,” about a traveling private detective/gunslinger, and went on to be a regular guest star on numerous television series, sometimes as a babyface, sometimes as a heel. Towards the end of his career, he landed co-starring roles in numerous studio films such as The China Syndrome and Gremlins.

By the 70s, Larry himself was driving a horse-drawn carriage in Central Park for tourists, and was also reported to be occasionally homeless. He continued to work as an actor, albeit much more sporadically, and was cast in Andy Warhol’s Bad in 1976, and in John Cassavetes’ Gloria in 1980. I would have paid to be a fly on the wall to watch a conversation between Warhol and Larry, which could have easily degenerated into a prequel for I Shot Andy Warhol.

But then business began to pick up again. Another legendary director, John Huston, helped spur on yet another comeback cycle when he cast Larry in a supporting role in Prizzi’s Honor in 1985, alongside Jack Nicholson and Kathleen Turner. Then, Larry landed a larger role in Stephen King’s Silver Bullet, followed by a very prominent part as Ryan O’Neal’s father, in 1987's Tough Guys Don’t Dance, written and directed by fellow Boys’ High alumni, Norman Mailer. He had a recurring role as Sgt. Jenkins on “Hill Street Blues,” where he even was given the last line of the series, picking up the phone and simply saying, “Hill Street” in his gruff voice.

Violence always followed in the footsteps of success with Larry, though. Another clipping recounted an incident in 1991, just three years prior to our then-current journey with him, where a drunk Larry fired a .357 magnum in his apartment, which blasted through the wall into the adjoining apartment. He apparently was shooting near, or at, his nephew. The nephew was Michael Tierney, the son of Edward Tierney, youngest brother of Larry and Scott Brady/Gerard Tierney. Edward also had an acting career, first introduced to the public playing the long-suffering younger brother to a recently released convict played by Larry, in The Hoodlum, in 1951, and then later in B-pictures such as Liane, Jungle Goddess. No one was hurt in the recent shooting, but Larry had been arrested.

This is who Mike and I had been dying to get onto our film. We had a cast and crew to worry about, and the date we could have the night club Savoy, for shooting, was locked. If we had to stop shooting because of some on-set problem, it would likely be months before Savoy would be open for us again, if ever.

In the late afternoon, Mike and I met at my 16 mm workprint-infested apartment on Saltair Ave., where we read through the press clippings I had printed out from microfilm. Our partner and attorney Matt joined us, as Mike also had some Larry research of his own that he had done. A mutual friend named Melanie had recently worked closely with one of the investors in Pulp Fiction, which hadn’t been released yet but which anticipation for was very high, and Melaine had some Tierney stories that her boss relayed, about the shoot of Reservoir Dogs in 1991. We called Melanie via speakerphone, which we gathered around eagerly.

“Lawrence Tierney and Quentin Tarantino nearly killed each other!”Melanie recounted. Apparently, Tarantino and Tierney got into a near fistfight/shoving match after Tierney kept forgetting his lines, and Tarantino fired Tierney, who stormed off the set and down the street to a bar, where he proceeded to get loaded. Later that day, a drunk and enraged Tierney fired his Magnum in his apartment, either at his nephew Michael Tierney, or in his general direction. A large hole was blown in the wall. I had just read the story about shooting the gun in the apartment in the library research, of course, but hadn’t realized the incident was a direct result of a very bad day on the Reservoir Dogs set.

“And he pulled a knife on Jerry Seinfeld!!!” exclaimed Melanie, as a segue way to her final Tierney tale. Now, the real details of that “Seinfeld” story only became quite well known years later, but at the time, all Melanie could relay was that Larry managed to ruin for himself what would have been a lucrative recurring role as Elaine’s father, Alton Benes, on “Seinfeld,” in 1990, when he tried to steal a large knife from the kitchen set in Jerry’s apartment. Jerry Seinfeld himself confronted Larry about it, and Larry tried to make a joke of the situation, saying he took the knife in case he had to stab Seinfeld in the head with it, and mimicking that stabbing with the blade. He was quickly fired, although the one episode Larry did appear on, “The Jacket,” is considered a classic of the series. He showed his comedic chops in the episode, skills which he was seldom cast to use.

First-time director Tarantino reportedly had grand visions of including Larry in his later works, which could have seen Larry even cast in Pulp Fiction in some supporting role. Early drafts of Reservoir Dogs had contained a dedication of the script to Lawrence Tierney, but Larry had subsequently managed to incinerate this career bridge as well by his behavior on-set, turning uber-fan Tarantino into an adversary.

Most of the crazy Larry-related Reservoir Dog stories, as recounted by not just Tarantino, but also co-stars Chris Penn, Michael Madsen, and Tim Roth, weren’t really reported in the press until years later, largely when Tarantino and the cast started doing interviews reminiscing about the making of the film for landmarks like the DVD release. Tarantino would recount in an interview with The Guardian, “Tierney was a complete lunatic by that time — he just needed to be sedated. We had decided to shoot his scenes first, so my first week of directing was talking with this ***king lunatic. He was personally challenging to every aspect of filmmaking.”

It was pretty obvious that we had to drop the Tierney cameo. Sexy Dominatrix hurling her whip around willy-nilly had nearly cost Mike an eye. Imagine if Larry attacked one of us, or one of the crew, or even Hill.

If I didn’t call Tierney, he might never call me again. However, formal termination of the relationship was probably advisable, according to attorney Matt, who was concerned I had already made a verbal contract with Tierney. Meaning that Tierney could now come after us for the promised $700 whether we shot with him or not.

This had been a long day already. Mike and I decided we’d just tell Tierney in the morning that the shoot was off for money reasons, not actually fire him, and hopefully that would end things and he’d forget about us.

As that evening’s work/entertainment, I had already picked up three more of Tierney’s most famous early films at the Santa Monica-based speciality video store Vidiots: 1945’s Dillinger, as well as Born to Kill, and, of course, The Devil Thumbs a Ride, both released in 1947. It seemed pointless to watch them now, but we popped Dillinger in anyway, with the intention of watching just for a few minutes. We couldn’t turn it off.

Dillinger was Tierney’s first starring feature role, and the film that made him a star after RKO loaned him out to the low-budget “Poverty Row” producers at King Brothers and Monogram Pictures. Directed by Max Nosseck, Dillinger was reportedly made for some $65,000, and was done on such a shoestring that it included a “smoke bomb” bank robbery scene that was edited in from the 1937 Fritz Lang film You Only Live Once. Even with his lack of leading role experience, which sometimes is evident in his occasionally flat line delivery here, Tierney radiates a magnetic screen presence. You really can’t take your eyes off him. The film went on to be a huge box office success, grossing at least 2 million on that small budget, and some reports had it as much as 4 million, in 1940s dollars. Tierney became an overnight star.

There were two more noir classics to go and the night was still young. While Tierney showed great promise in Dillinger, the two RKO films we watched next, The Devil Thumbs a Ride and Born to Kill, showed him really come into his own, on films with larger budgets. In the case of Born to Kill, the film also benefited from the directing skills of one Robert Wise. Like Dillinger, the RKO productions were also filled with terrific supporting actors, who were great foils, of a variety of stripes, against Tierney’s slow-boiling presence.

The 1940s were a time in Hollywood of great faces in the undercard, and Born, in particular, has strong supporting work from the likes of Elisha Cook Jr., as Tierney’s miscreant best friend, in a nice visual continuation of their criminal partnership seen first in Dillinger, where he played one of Dillinger’s gang. Larry was at his best when he had a good foil to play off of, and Cook Jr., nervous and much smaller physically than Larry, completed a great onscreen pairing.

This trio of films quickly schooled us that Tierney was more than just the photogenic character guy from Reservoir Dogs. He was a legit great actor. This is why he had so many chances at comebacks. He was the definition of acting lightning in a bottle. Not always easy to control, to be sure, but when he delivered, he delivered huge. Tierney radiated malice onscreen in a way that few performers ever have, before or since. In both Born and Devil, he never appears to be acting. It’s more like the real-life actual version of his degenerate criminal characters was dropped into the film. In a time when special effects were in shorter supply in films, Tierney was a special effect via his unique and riveting screen presence. At the time of the RKO films, he was frequently compared to Robert Mitchum, who was also in trouble with the law often, although not as much as Tierney was. Mitchum obviously also shined in his portrayals of criminals, but there was an occasional warmth that peaked through with Mitchum, a humanity… that Tierney seemed to lack, onscreen at least. When Tierney did crack a joke, or attempt a twinkle, it only made him scarier to the audience, even if it briefly fooled or charmed his hapless victims in the actual film. Mitchum could play a hard-boiled hero and have the audience root for him. Tierney, maybe not. If Tierney had portrayed the villain in The Night of the Hunter instead of Mitchum, that already haunting film about an evil preacher chasing two children may have been so terrifying as to be difficult to watch.

After Born to Kill unspooled to its bleak ending, which was the opposite of life-affirming, followed by the famous RKO logo, Mike and I had come to the same conclusion. One of us just had to say it.

“You know, it’s worth trying. This could be great. This guy has more great performances in him,” said Mike.

“Tarantino had to squeeze what he got out of him,” I cautioned. “You can see him cutting around Tierney sometimes, when there were longer dialogue passages.”

“But he had a lot more scenes with Tarantino,” Mike correctly noted.

“We only have this one to get through.”

“And we’re going to give him a chance to show those comedic skills, that Jerry Seinfeld lost out on,” I added. “We’re going to have to warn the cast and crew before we shoot, though. Let us handle him.”

“If one of us gets killed, just dedicate the movie to me,” Mike said.

“You’re directing, so it probably will be you he gets first,” I half-joked.

So, after being ready to cut and run from the possible madman just hours earlier, we had now decided we had to do this. There were maybe still levels of greatness in Tierney that had never been tapped. We would be the tappers.

Filmmaking folly, thy name is youth.

Because nothing good ever comes easy, the next morning a new player entered the game. The call was from Michael Tierney, the same nephew who had been shot at, or near, in 1991. He seemed affable, but also businesslike. He wasn’t ringing to be my new pal.

“Larry has a lot of young filmmaker friends, and he likes to help them out. I just try to look out for my uncle and help in his management,” said Michael.

I agreed that it was important for a family member to be watching out for Larry, and it was, but now I knew we had somebody else in here who could gum up the works. Up until now, I had only been dealing with Day Larry or Night Larry, but now I had Nephew Larry in the mix. Getting to a contact might have just gotten much harder, or maybe it was going to be easier, if his nephew could handle the Day/Night Larry side of things. We were about to find out.

“Maybe we’ll get Day for Night Larry,” Mike joked, making a reference to the 1973 Francois Truffaut film. Cinephile humor. Actually, Day for Night Larry sounded like just what we wanted. Calm with moments of fire, hopefully all for the camera.

Michael Tierney suggested we all meet the next day, so Larry could get to know us a bit, and in Michael Tierney’s words, “Go over the script pages you sent and some concerns he had.” The whole thing now seemed like it was tenuous all over again. I restrained myself from blurting, “Whoa! Wait just a minute.” Larry maybe didn’t like the script pages, which was sort of fine, because we could rewrite them, but we were running out of time. The shoot at Savoy was in two weeks.

I again called Joey, our original liaison to Larry, who Larry didn’t seem to actually remember, for advice. Joey said that he knew Michael and that I shouldn’t be worried about dealing with him in a high-tension negotiation.

“Michael’s a ***king actor,” Joey added with a shrug. Only in L.A. could that sentence be understood to speak volumes, but also possibly mean little at the same time. “A ***king actor” could mean a performer who takes his craft very seriously. It could mean a flaky actor who sleeps on friend’s couches and never gets work. Or it could mean a giant pain to our negotiation. We were going to find out shortly.

The next afternoon, which was a Sunday, Mike and I set out to meet the Tierney’s at the venerable Hollywood Athletic Club, a cavernous bar and pool hall that had found new popularity with hipsters in recent years, and which Larry himself picked for our meeting. The Athletic Club had originally started as an actual health club in the 1920s, and its membership included a veritable who’s who of the motion picture industry of the time, such as Charlie Chaplin, Walt Disney, Jean Harlow, and Douglas Fairbanks Sr. Larry had once lived above the place sometime during his 40s and 50s heydays. If Larry had been banned from the place back then, as he was from so many Hollywood hotspots during his hard-drinking prime, the current owners weren’t likely aware.

Drizzling cold rain greeted us at the valet. Typical March weather in Los Angeles. A decent crowd inside for drinks and lunch on a Sunday afternoon, with a few people playing pool as well. A top production designer couldn’t have stage-managed a better location for our big sit-down with Lawrence Tierney. The shadowy lighting, the classic art deco design, it all screamed noir. There was no point in living in L.A. if you couldn’t occasionally imagine your life as part of a classic movie, even with the knowledge that supporting characters like us had a high mortality rate in Lawrence Tierney pictures.

Michael Tierney had already arrived, standing by the bar when Mike and I entered. He was a few years older than us, with slightly longish hair, and a bowling-style shirt. Michael greeted us with handshakes, saying that his uncle was walking down the street to join us, and that he was sometimes late, so we should get a table.

The three of us sat down in the rear of the dining area, and made some small talk. The crowd was mostly younger types in the 20s, our general age range. Which made Larry’s entrance stand out all the more. Standing 6'1'’, wearing a dark trench raincoat, he first appeared at the far end of the bar, his bald dome looming above most of the other patrons. By far the oldest person in the place. As he made his way to our table, a number of heads turned. Some stopped playing pool for a moment. Maybe they knew him from Reservoir Dogs, or the one “Seinfeld” episode, or there were a few cinephiles who knew his cinematic history, or they were all staring just because he was a unique and imposing presence.

After how many crazy phone calls and conversations and debates amongst us, I couldn’t believe we were actually here together. My heart raced.

Larry smiled a small amount when we were introduced, but he didn’t waste much time dashing our hopes of ever making this work.

“Fellas, I have some bad news about this picture.”

He just let that sit there.

Michael Tierney chimed in, rescuing the moment to a degree, “Larry found out this morning that he has an offer for at least a week on the new Ivan Reitman movie. $10,000 a day. He has to leave next Thursday.”

That would put him already out of town by the time we had to shoot at Savoy. Hoping that it was maybe just the proverbial Hollywood “creative differences” here, I injected, “Larry, was it the script? We can work on that. We wrote it for you, so we can change it…”

“Naw, not the script. The script is fine. I mean, you have some stuff in there that I don’t know… I tell the guy to take his clothes off…,” he laughed. Mike and I all joined in the laughter, still hoping to save this.

Michael Tierney added, “Look, Larry’s willing to do your movie if you can still do it when he gets back. We just don’t know when that is going to be yet.”

Larry said, “$10,000 a day is not something I can screw with. You know, I’m looking at land in Arizona right now.”

I still blame the great state of Arizona in part for this, but that was that. Larry wasn’t saying no to us, but it wasn’t likely something we could wait any longer for. After all of the sturm and drang, this had simply ended with a polite “no thank-you.”

Larry added, “I know you guys worked hard on this picture, so I wanted to tell you in person.”

What could we say to that, other than a thank you in return? It didn’t hit me back then, because I was an egotistical young artist, and thought that of course Larry should do our scene. We needed him, but we were also doing him a favor. We were going to be huge in this business. I mean, what else was Larry doing anyway? Working with frigging Ivan Reitman? Larry was a guy who had gone the distance in show business, not once, but several times. He also managed to epic-ly dynamite his career several times, but nonetheless, this couldn’t be looked at in any other way than that he was doing us the favor in even considering the film.

The Larry Tierney we met that day was the one I read about later in parts of Burt Kearns’ book, in some recollections. Charming and funny, there was nothing violent or explosive about the guy in front of us. He was encouraging to two young filmmakers who he likely didn’t have to have this meeting with. But, based on the myriad experiences of others, the occasional madman of legend was likely to also make an appearance, with or without alcohol, if you spent enough time with him. He was one complicated character.

Quentin Tarantino would add the following about working with Larry years after Reservoir Dogs, which is quoted in the Burt Kearns book, “If you’ve ever seen The Devil Thumbs a Ride, that could be called ‘The Lawrence Tierney Story,’ because it’s about some nice guy who’s driving down the street and Lawrence Tierney’s hitchhiking on the side of the road. And you stop to pick him up. You’re having a good day and you’re a nice guy, but because you bumped into Lawrence Tierney, he’s gonna ruin your life. From that moment on, your day’s gonna be **cked and your life is going to be ruined while he’s in your presence.”

Based on that analogy, perhaps it is best that things ended when they did and my last memory of Larry was a fond one that I cherish. He gave Mike and I each a very firm handshake in the light rain outside the Hollywood Athletic Club and said, “Fellas, best of luck with your picture.” Then, he walked down the street with his much younger nephew, who he had once fired a gun at, or in the general direction of, and he was gone.

Although Michael Tierney’s injecting himself into the proceedings really annoyed me at the time, because I felt like he was going to get in the way of his uncle shooting with us, I also believe in retrospect that he was keeping an eye on his uncle and making sure that no one took advantage of him. These were the acts of a loving family member, and I’ve had to do the same for my own family, and their own business interests, as years have progressed. The Tierneys were an acting family. Different than the Baldwins or the Barrymores, to be sure, but then, every family was different.

Lawrence Tierney died on February 26, 2002, of pneumonia, which had been preceded by a series of strokes, one of which was sometime in 1995, only a year or so after our meeting. He was 82. Larry had outlasted by decades both of his younger brothers, who, by all accounts, did not live anywhere as hard as he did. That was a very high bar, granted.

After Larry’s death, literally dozens of stories came out, largely in tribute to him, from other young filmmakers and writers, similar to ourselves in career stature (as in not much career stature at the time) and who Larry had befriended, and vice-versa. Some of them, like Chris Gore, ended up actually shooting projects with Larry. Others developed friendships. The old Hollywood had abandoned Larry long ago, for the most part, but the younger upstarts viewed him as a legend and a star. Some of their stories would become the stuff of indie filmmaker legend. Larry crashing on their couch for a night, and then not leaving for a month. Phone calls in the middle of the night to pick him up at the Formosa and other classic Hollywood bars he still haunted in his 70s. Randomly throwing punches at people. Bouts of kleptomania, and public urination, including one occasion in the back of the Egyptian Theater at an American Cinematheque screening of Born to Kill, in 1999, as recounted in an epic blog post by Eddie Muller.

The Ivan Reitman movie, which the Tierneys didn’t identify by name, was Junior, which starred Arnold Schwarzenegger, as a man who gets pregnant, and also starred Danny Devito and Emma Thompson. Larry played a moving man with a line or two in Junior. Not a memorable role, but at $10,000 a day, I couldn’t blame him for forgoing our production for this one. In retrospect, I wonder if Larry had any of his “moments” with Arnold around. Even at his advanced age, I would not have bet against Larry in a fist fight with 40-something Schwarzenegger.

Junior also maybe put Larry back on the map with the studio casting directors for one last ride in the biggest film of 1998, Armageddon. Larry shot a noteworthy scene for the Touchstone Pictures smash hit, where he played Eddie “Gramp” Stamper, the elderly father of the Bruce Willis character, who goes to visit him before the likely suicide mission against the asteroid. The scene was cut from the theatrical version, but it was included in the Director’s Cut DVD and is easily found on YouTube. Directed by Michael Bay, and produced by Jerry Bruckheimer, Armageddon was the top-grossing worldwide feature film hit of the year. Despite the scene being cut, Larry was playing in the biggest leagues of his career for his final act. He also kept working in small indies, and with family, right until the end. His last actual recorded role was in a low-budget movie called Evicted, in 1999, which co-starred and was directed by his nephew Michael.

Michael Tierney later went on to become one of the most successful male porn stars in the world, under the stage name “Joe Blow,” but has apparently since retired from porn. He starred in over 350 exotic pictures and was nominated for two Adult Video Awards, the porn equivalent of the Oscars.

The weight of Larry’s legend seemed to be felt by Michael, long after the older Tierney’s passing. While promoting a documentary about his life called The Last Days of Joe Blow, Michael explained in an interview with Australian blogBeat, “Growing up in somebody like Lawrence Tierney’s shadow is a little intimidating because you wanna be an actor and you can’t be who he was, because there’s only one Lawrence Tierney. Going into porn was kind of my, ‘F you,” to the whole being somebody’s nephew. I’m gonna be Joe Blow and start with a new name and let’s see how I do on my own without any training wheels in a completely foreign territory.”

In the end, we never got “the Cameo” in our film, and wound up shooting the scene at Savoy with a basically unknown, but gifted, actor named Scott Murphy as Roger, and who did a terrific job.